When I was a debutante, I often went to the zoological garden. I went so often that I was better acquainted with animals than with the young girls of my age. It was to escape from the world that I found myself each day at the zoo. The beast I knew best was a young hyena. She knew me too. She was extremely intelligent; I taught her French and in return she taught me her language. We spent many pleasant hours in this way.

For the first of May my mother had arranged a ball in my honour. For entire nights I suffered: I had always detested balls, above all those given in my own honour.

On the morning of May first, 1934, very early, I went to visit the hyena. “What a mess of shit,” I told her. “I must go to my ball this evening.”

“You’re lucky,” she said. “I would go happily. I do not know how to dance, but after all, I could engage in conversation.”

“There will be many things to eat,” said I. “I have seen wagons loaded entirely with food coming up to the house.”

“And you complain!” replied the hyena with disgust. “As for me, I eat only once a day, and what rubbish they stick me with!”

I had a bold idea; I almost laughed. “You have only to go in my place.” 1

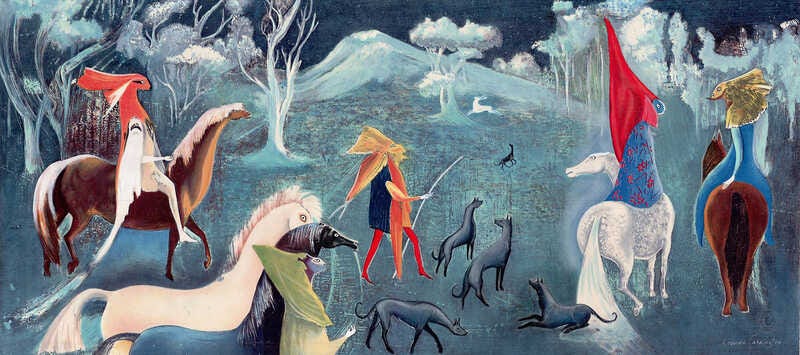

Dear coven, with May just around the corner, I could not help but choose The Debutante (1939) by Leonora Carrington as this week’s enchantment - a weekly series in which I cover works motivated by magic.

The story is a dark, comedic reflection of Leonora Carrington’s experience as a debutante. Much like Carrington, the titular character is reluctant and defiant, drawn to strange creatures such as a hyena in the zoo.

The zoo is a significant meeting place - it is a space in which animals are exposed to observation, animals which are representatives of the irrational world; it ‘keeps these untamed forces of nature in check, caged and repressed, in this atmosphere man need not fear an upsurge of animal's unchanneled impulses.’ 2 Carrington embraces those impulses, and the girl in her story befriends the wild animal.

In The Debutante the hyena attends the ball while the girl hides away in her room, reading Gulliver’s Travels (1726) by Jonathan Swift - a favoured choice for a young girl in a state of rebellion, think Jane Eyere. In real life, however, Carrington had to be presented to society. The 1934 London season balls, the Ascot races, and the eventual 1935 debutante presentation of Leonora Carrington at the court of George V, felt like a diabolical high society nightmare to the artist. The young girl had already been expelled from a number of institutions and had fallen out of favour with her father and mother. So, they stuck feathers in her hair and put her in a dress in the hopes that her unyielding curls and ferocious nature could be purified with white satin.

When she spoke on the event Carrington recalled she was most angry about the notion of ‘being put on the market’, she felt that she was being ‘put up for sale so her parents could get rid of her’. 3

This parade of forced womanhood led to Carrington’s desire to tap into the feral, undomesticated side of femininty. After all, when forced to perform, whom amongst us has not wished for a feral animal to take our place?

Carrington’s choice of the hyena was not accidental, she held a strong fascination for the animal:

Hyenas particularly attracted me in the zoo…Their great virtue is that they eat garbage. I’m like a hyena, I get into garbage cans. I have an insatiable curiosity. 4

This animal, whose nature is to live in a matriarchal pack led by an alpha female, demonstrates bestial nature that in Carrington’s words, ‘resides in everybody’. 5 This might be true, but Carrington does not portray just everybody, she specifically portrays women this way, which is in profound contrast to how male surrealists categorised women.

In The Debutante, the hyena is adorned with gloves, shoes, a new frock, and, grotesquely, a devoured maid’s face. The animal struggles to eat the entirety of the maid, so her legs are placed in an embroidered bag and stored in the closet for later consumption.

The narrative takes place on the first of May, which I see as an allusion to Beltane, the Gaelic May Day festival marking the beginning of summer. Carrington’s deep knowledge of folklore and esoteric practices is evidence for my assertion.

The day is associated with druid magic, sacrifices to a god named Beil and bonfires. 6 What is especially intriguing in the context of The Debutante is the significance of cakes in Beltane – despite its esoteric roots, the celebration was once an attempt to prevent the spread of witchcraft. During these ceremonies the sharing of a May Day cake was customary; whoever received a piece marked with charcoal was singled out as a scapegoat, subsequently became a figure of terror and was then pelted with eggshells to diminish the power of all witches. 7

In The Debutante the animal within can only be hidden for so long and the fraudster is quickly discovered by the mother during dinner. Keeping May Day cakes in mind, the hyena’s remark does not seem coincidental:

My mother entered, pale with rage. “We were coming to seat ourselves at the table,” she said, “when the thing who was in your place rose and cried: ‘I smell a little strong, eh? Well, as for me, I do not eat cake.’ With these words she removed her face and ate it. A great leap and she disappeared out the window. 8

There is a matriarchal order at play - the Mother represents order, convention and traditionalism, while in turn the daughter rejects these factors through her friendship with beasts like the hyena. This is not coincidental, it is with her mother that Carrington visited the zoo, it is beside her mother that she stands, dressed as a debutante.

We see a duplicate of the hyena in Carrington’s painting. A flowing mane of hair, a wide-eyed hyena and a white rocking horse decorate the canvas of her Self Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) (1937-38). The process of painting began in London in 1937 and was then completed in Paris in 1938. During this time, at the age of twenty, Carrington fled her family home with painter Max Ernst and became an active member of the surrealist circle. It was a pivotal time in Carrington’s life and so was the Self-Portrait, which featured symbols and motifs that became constants in her work, such as childhood memories, domestic spaces drenched with magical energy, animal familiars, and self-referential elements are notable in this painting.

There is a hypnotic element to Carrington’s painting, and the psychic centre to the unfolding drama on the canvas is Carrington. Sat in the Victorian styled chair, her hand raised in the sign of malediction, or perhaps an incantation, her figure is entirely immobile. There is also a play of gender roles – the chair Carrington is sitting on suggests a sensual, feminine shape, which juxtaposes the artist's traditionally masculine dress and stance. The carved armrest of the chair echoes the shape of her resting hand, just as the boots she is wearing mimic the chair’s legs. The elegance of the chair underscores the traditional idea of femininity that was expected of her – one that can only be identified with all the beauty, grace, and stiffness of a piece of furniture.

In the painting, it appears that Carrington and the hyena hold a significance to one another, especially given their mirrored body language. It is as if the artist has manifested her entire being into the hyena, forming a connection between the two with her pointed hand gesture, and their interconnected shadows on the floor.

It has been suggested that Carrington and her hyena are like a witch and her familiar; they form a bond, they share mutual benefits, and the familiar serves the witch as a loyal protector. It is also said that witches can transform into animals. Perhaps the hyena does not signify an outward companion, but an inward force, growling and begging to be unleashed.

The Debutante marks the hyena’s first appearance in Carrington’s oeuvre and as Beltane is fast approaching, this seemed like the perfect occasion to re-visit this short story.

If you wish to discover more works motivated by magic, please consider subscribing and following this newsletter’s visual companion.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

Eggs, Alchemy, and Surrealism: An exploration of the significance of eggs in folklore, magic and Surrealism.

bibliography

Aberth, Susan. Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art. London: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, 2010.

The Flowering of the Crone: Leonora Carrington, Another Reality. Documentary. Reel Women Media, 2015.

Carrington, Leonora, and Gloria Orenstein. The Oval Lady: Surreal Stories by Leonora Carrington. Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1975.

Carrington, Leonora, and Marina Warner. The Debutante and Other Stories. London: Silver Press, 2017.

Carrington, Leonora, and Marina Warner. The House of Fear: Notes from Down Below. Michigan: E.P. Dutton, 1988.

Keating, Geoffrey. The History of Ireland. London: Legare Street Press, 2022.

Knapp, Bettina L. ‘Leonora Carrington’s Whimsical Dreamworld: Animals Talk, Children Are Gods, a Black Swan Lays an Orphic Egg’. World Literature Today 51, no. 4 (1977): 525–30.

Meskimmon, Marsha. The Art of Reflection: Women Artists’ Self-Portraiture in the Twentieth Century. London: Scarlet Press, 1996.

Leonora Carrington and Marina Warner, The Debutante and Other Stories (London: Silver Press, 2017).

Bettina L. Knapp, ‘Leonora Carrington’s Whimsical Dreamworld: Animals Talk, Children Are Gods, a Black Swan Lays an Orphic Egg’, World Literature Today 51, no. 4 (1977), 526.

The Flowering of the Crone: Leonora Carrington, Another Reality, Documentary (Reel Women Media, 2015).

The Flowering of the Crone: Leonora Carrington, Another Reality, Documentary (Reel Women Media, 2015).

Leonora Carrington, The House of Fear: Notes from Down Below (Michigan: E.P. Dutton, 1988), 1.

Geoffrey Keating, The History of Ireland (London: Legare Street Press, 2022).

Venetia Newall, ‘Easter Eggs’, The Journal of American Folklore 80, no. 315 (1967), 10.

Leonora Carrington, “The Debutante” in The Oval Lady: Surreal Stories by Leonora Carrington, trans. Rochelle Holt (Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1975), 23-24.