Eggs, Alchemy, and Surrealism

An exploration of the significance of eggs in folklore, magic and Surrealism.

My great-grandmother, like most of her neighbours, kept chickens. While she lived only half an hour away, this rural aspect of her life felt distant, curious and, at times, frightening. Perhaps it was her tenderness towards the chickens that I did not understand, my hands only familiar with the softness of dog fur and the indifferent sniffs of cats.

I can still picture her, sat in bed, chicken cradled in her arms like a baby. This gentleness did not spare a select few chickens from ending up on the dinner table at her own hands. That was her life. There was softness and there was death, but there was also life, so much life. From the stray kittens raised in cardboard boxes, to the howling hound-pups next door, life was brimming from every corner of the house.

And, of course, there was the eggs.

Mornings were for margarine toast and collecting eggs. I was always on edge around the chickens, the clucking and the feathers were too much for my skittish sensibilities, but I enjoyed collecting the eggs. I remember holding an egg in my hand and the warmth it emulated. It felt so fragile, yet so very important.

Dear coven – Happy Easter. This year, the Orthodox Easter of my home-country coincides with Easter in England. I have not been at home for Easter in a few years, so I have not had the chance to celebrate in the same way for a while, which has made me ponder on folklore, tradition, and magic.

At the centre of it all lies the egg.

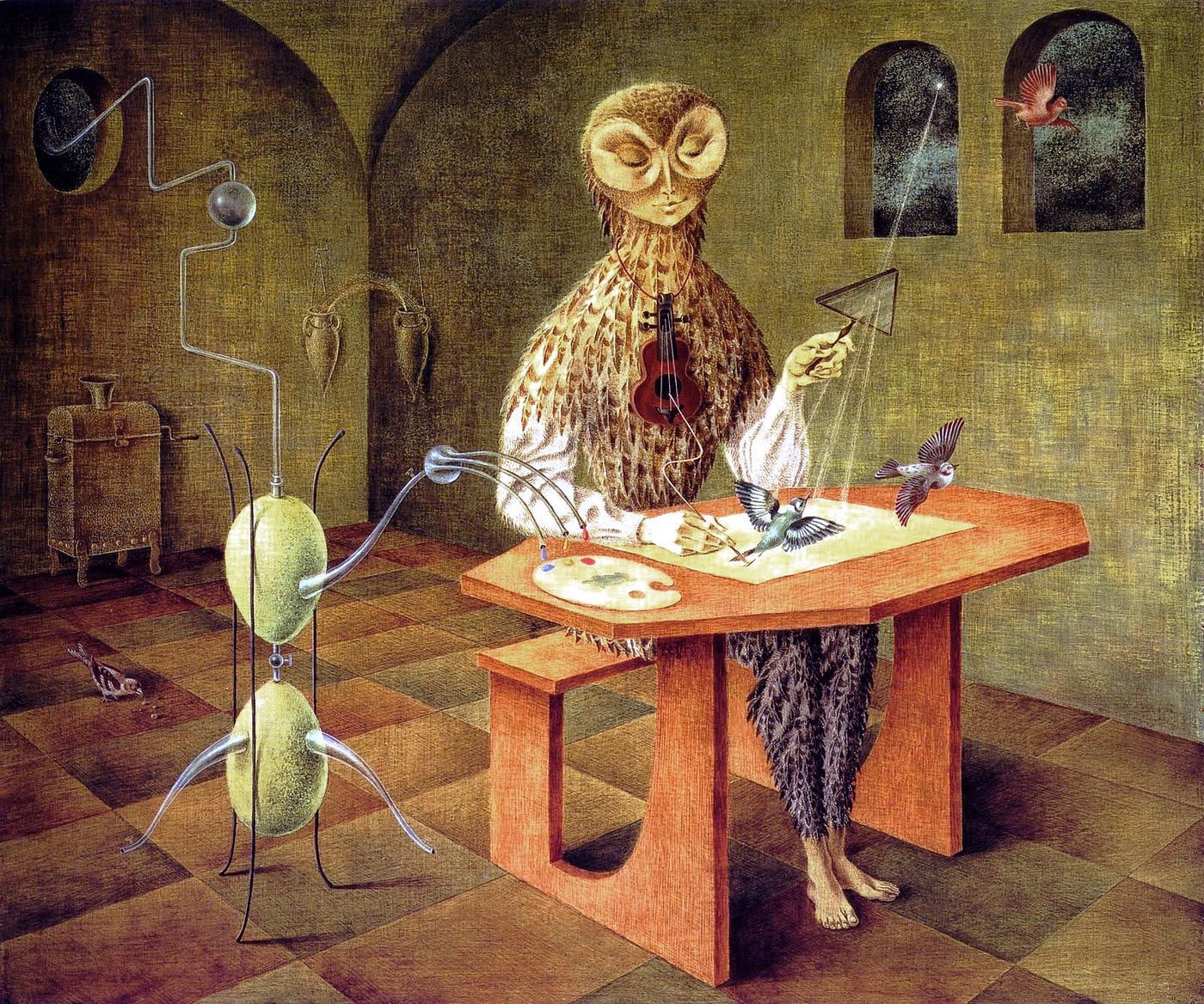

So, today I would like to talk to you about eggs and how a line can be drawn from archaic beliefs to alchemical practices, to the art of female surrealist artists such as Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Leonor Fini.

Let us start at the beginning. Literally.

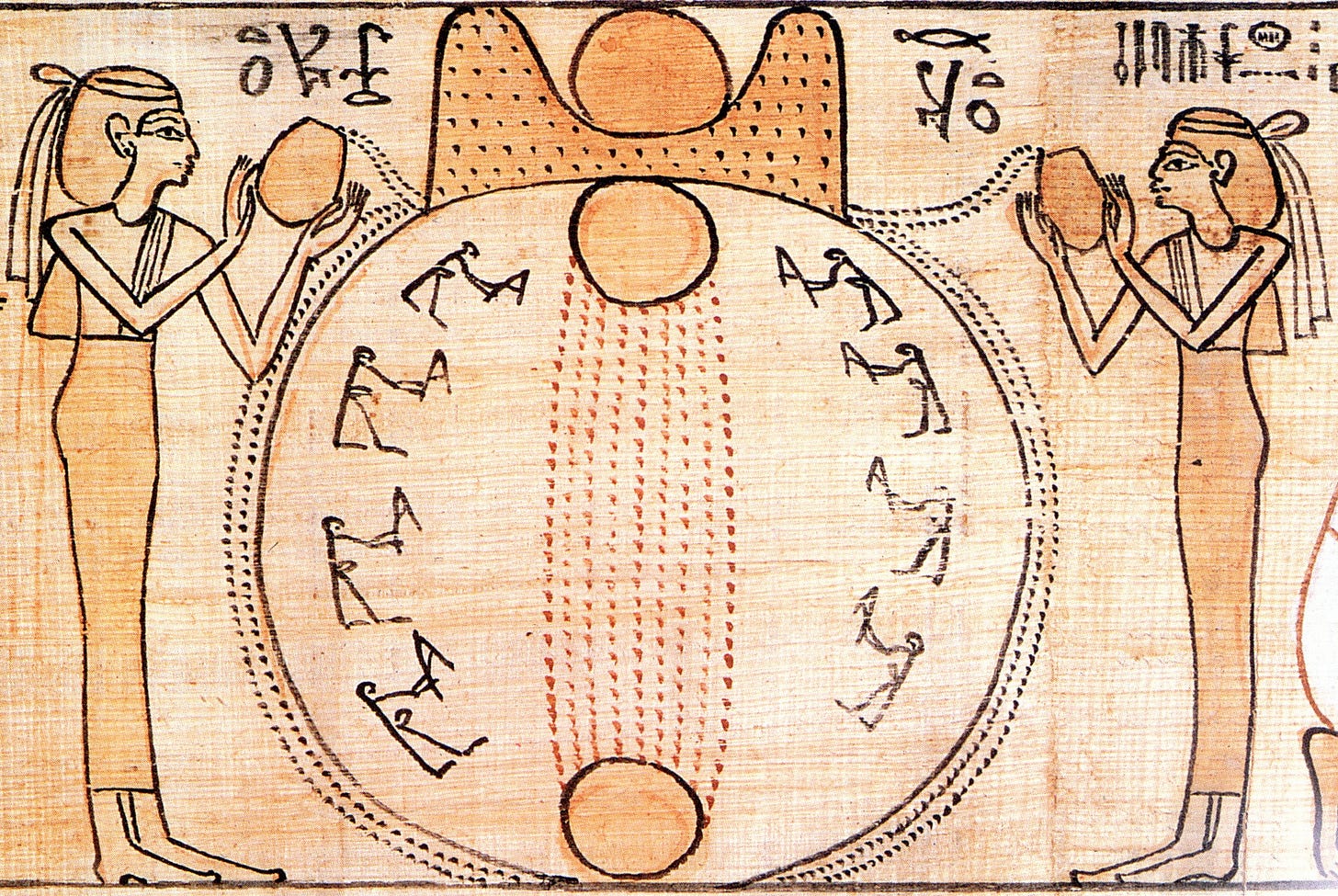

The cosmic egg motif is a persistent symbol of creation myths, the first recorded reference to it occurs in an Egyptian papyrus of the New Kingdom period:

O Egg of the water, source of the earth, product of the Eight, great in heaven and great in the underworld, dweller in the thicket, chief of the Isle of the Lake of the Two Knives, I came forth with thee from the water; I came forth with thee from thy rest. 1

The idea of a primeval egg, which hatched the Sun god occurs frequently in Egypt, and it extends across the world. The Chandogya Upanishad describes the original act of creation as the breaking of an egg in two pieces. The cupolas of Buddhist stupas literally represent the cosmic egg of creation. In Fiji, the origin of man derives from Ngendei, a fertility god, who hatched an egg similar to the world egg of the Polynesian Tangaroa. Chinese legends speak of the first being, Pangu who appeared from the cosmic egg.

If we must wonder which came first, my great-grandmother’s feathered friends or the egg, the answer seems obvious – even chaos was thought to exist as an egg which contains the principles of matter.

The potential of eggs did not cease with creation myths of ancient societies. They were later used for protection and divination - in England, an egg laid by an old hen would protect the farmyard from ill; if English girls wanted to know who their future husband would be, they could prick a newly laid egg and allow three drops of the white to fall into a bowl of water, the shapes that formed would provide the information. 2

If you wanted to do some fortune-telling of your own, it is said that the divinatory power of things is strongest at Easter (and Christmas). However, make sure you use the right size of egg, as small ones can be unlucky. 3 Eggs were used in love potions, in medicine, and for promoting fertile crops and animals, this kind of magical potential carries its own set of superstitions. It was unlucky to take them in or out of the house after sunset and a double yolked egg meant death was near. Sailors would not mention eggs at sea, nor would they sell them or take them on board when dark. 4

This was most likely to do with witches.

Given the egg’s magical properties, it comes as no surprise that they were associated with witchcraft. It was thought that a witch could sail over land and sea in unbroken eggshells. If you were to travel back in time to England, you would witness country folk smashing the shells of recently boiled eggs to prevent witches from using them as charms and vehicles.

So, where does Jesus fit into all of this? Let’s return to Egypt.

According to Egyptian mythology, the phoenix was believed to be a mythical bird which lives for hundreds of years, once its lifespan was completed, it died in flames, rising once more the egg it had laid. While it is not certain whether the phoenix originates from Egyptian, Greek, Chinese, or the many other cultures to which it has been assigned, it is considered that it became a symbol of resurrection for Christianity in the first century A.D. when St. Clement spoke of it in his Epistle to the Corinthians. 5

This means that, at a very early date, the egg itself also became associated with the process of resurrection. While customs connected to eggs were certainly a pre-Christian tradition, the Church did not oppose them, as eggs provided a potent metaphor for the transformation of death into life. In fact, there are a number of instances in which marble eggs, and even eggshells were found with the relics of saints, perhaps to stimulate their own return to life.

There are several stories that concern Jesus and eggs, specifically red eggs. There are several variations of the legend, one goes that the Virgin Mary gifted a basket of eggs to the soldiers guarding the Cross, hoping to stir some pity in them for her son. No one touched the basket, which remained at the foot of the Cross, the blood of Christ dripping on them, turning them red. 6 Another story goes that the Virgin Mary prepared a basket of eggs for Pontius Pilate, overcome with grief, her tears fell on the shells, forming dots of colour. You can also encounter such tales with Mary Magdalene as the protagonist.

In Eastern Europe, when we paint our eggs for Easter, red is the preferred and most traditional colour. It is cherished and important – red eggs were left on the graves of neighbours and family members, where women then perform a traditional dance in which the souls of the dead might join; young children were bathed in water into which the red egg had been placed; farmers took the first red egg into the fields and buried it to fertilise the soil and protect the crops from hail. 7

Within folklore tradition and belief, the egg plays a central role, but, historically, its use was not limited to protecting the crops, fortune telling and blessings. With this in mind, we have to take our third and final trip to Egypt.

The origins of alchemy can be traced back to Ancient Egypt, the fore founder being Hermes Trismegistus, later identified with Thot the Egyptian God of Arts and Sciences. There are other suggestions which point to Greek origins, the consolidation seems to be that while Egypt contributed to the practical nature of alchemy, the Greeks speculated on the nature of matter and the idea of transmutation itself. 8 I do not wish to delve too deep into this particular origin story here, it is truly fascinating, but that will be a deep dive for another day.

For our purposes today, let us first simplify alchemy to its core belief - within alchemy, the union of mercury and sulphur in their purest states could produce the most perfect metal, gold. Achieving this, was mastering the art of transmutation, which you could only accomplish with the right elixir, one that could be used from every kind of transmutation – the Philosopher’s Stone, as described by historian Zosimus:

This stone which is not a stone, a precious thing that has no value, a thing of many shapes, which has no shapes, this unknown which is known to all. 9

When Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great, Alexandria became the centre of the intellectual world. Travelling scholars contributed to the blend of influences in the study of alchemy – the Greek philosophers brought forth their Aristotelian theories on the basic composition of matter and transmutation, namely that all material objects were to be found in the four elements and that by altering their qualities, they could be transmuted into one another; the Egyptians solidified their reputation as expert artisans; the mystical ideas of Persian thinkers found expression in astrology:

Life on earth (microcosm) was only a mere reflection of events in the great world of the stars (macrocosm). 10

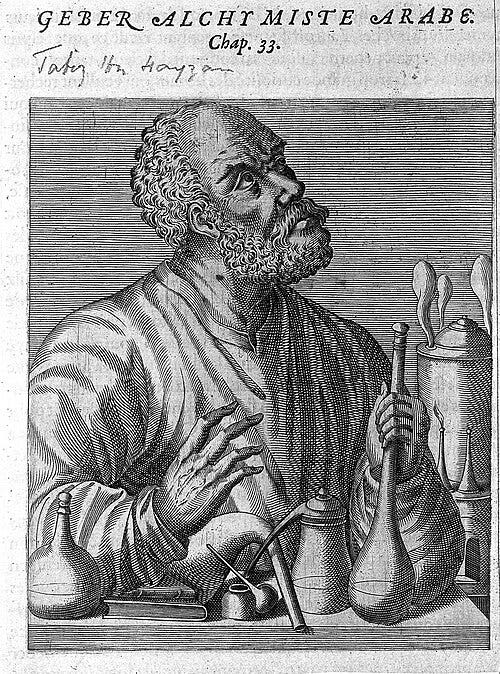

Alchemy travelled and developed. Syrian scholars in Persia began translating the works of Plato, Aristotle, and early alchemical writers into Arabic. Even more works were translated with the spread of Islam and Muslim alchemists such as Jabir Ibn Hayyan became adepts in the alchemical school of thought. Arabic scholars added ‘al’ as a prefix to the Greek ‘chemia’, thus giving us the word ‘alchemy’. 11

Once established in the East, alchemy eventually reached Spain and by the twelfth century A.D. and from there, it spread across Europe.

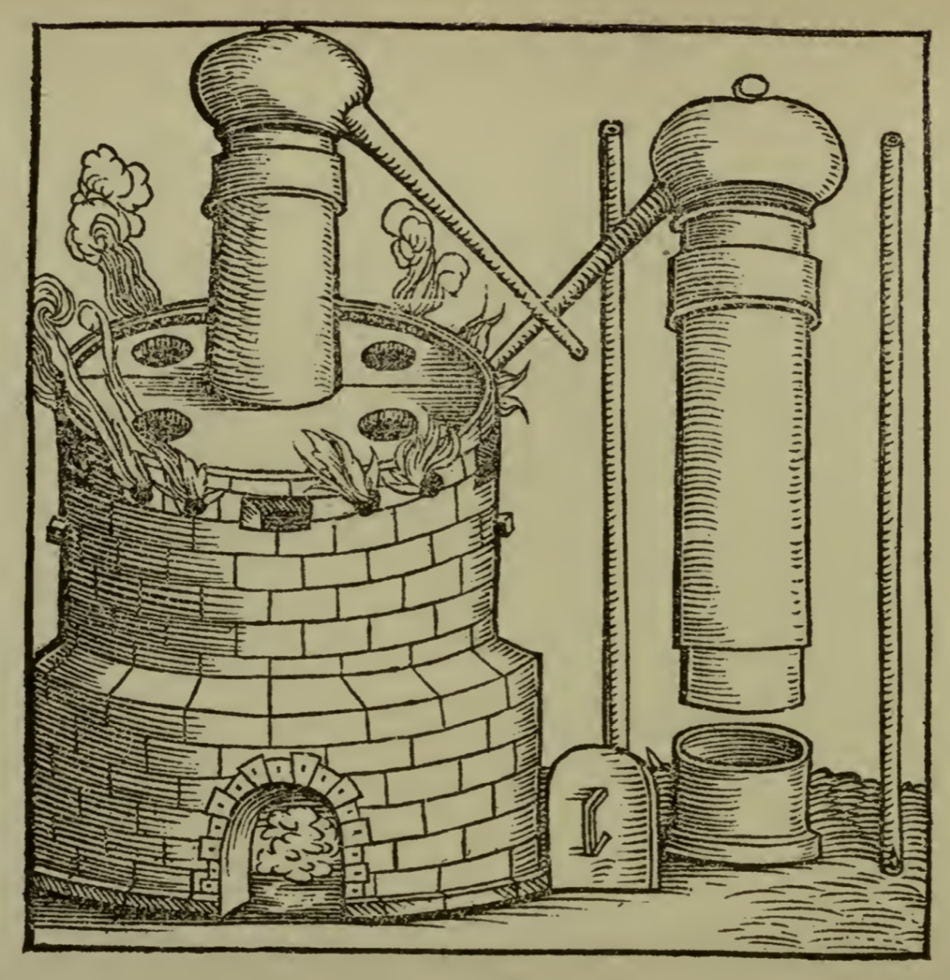

If we were to jump forward in history, we would find that, like those that came before them, the concern for the medieval alchemists was the preparation of the Elixir of Elixirs, the Quintessence, the Philosopher’s Stone, with the goal of then adding it to baser metals to induce their transmutation to gold and silver.

The Philosopher’s Stone did more than just produce precious metals. The aforementioned blend of Egyptian, Greek and Persian thought established the idea of the search for the perfect metal as an allegory for the human soul’s search for perfection. In the Middle Ages, this idea persisted, it was said that the stone could extend life, cure ailments, and provide its creator with wisdom and a strengthened sense of morality.

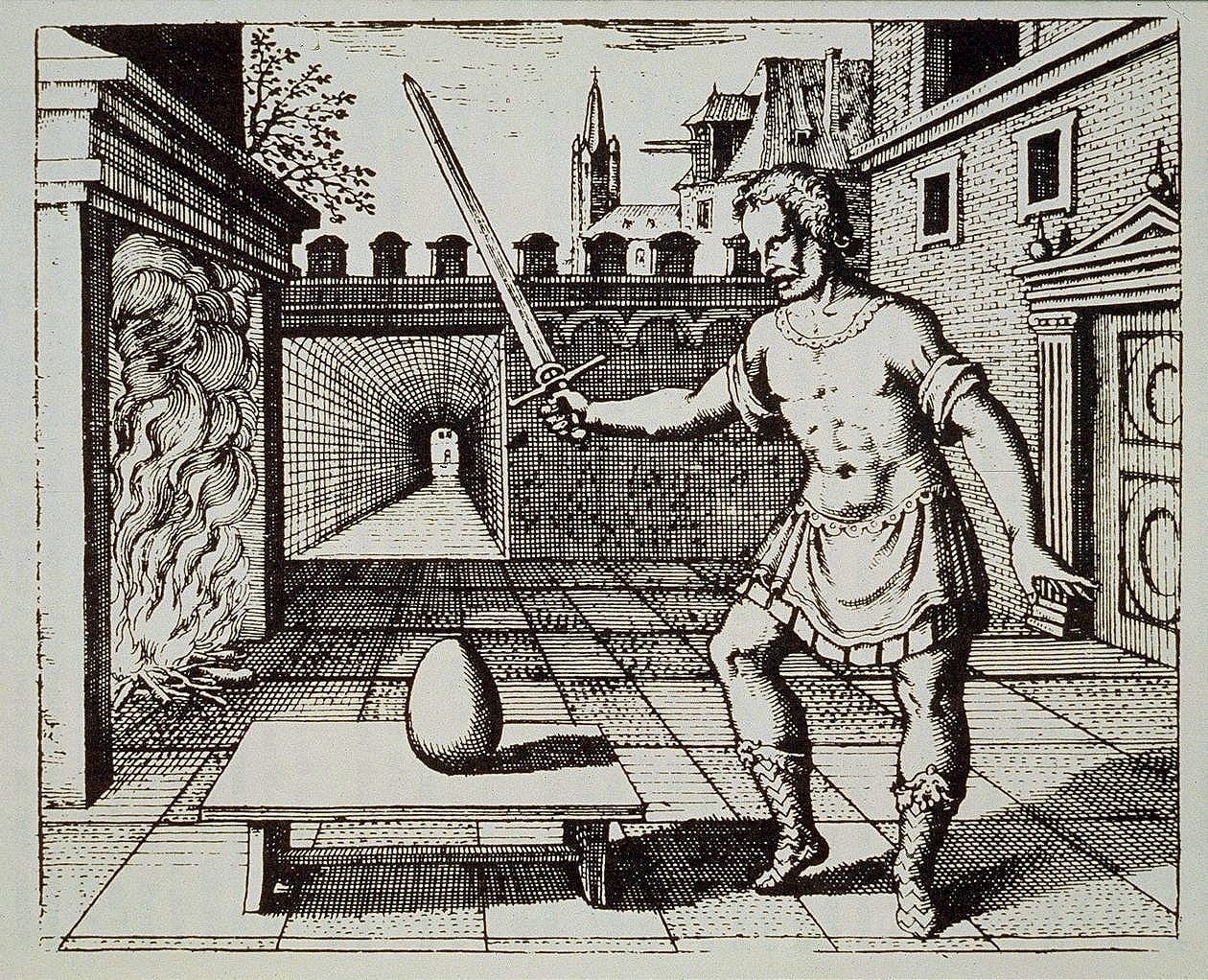

Alchemy was both a science and an art, one that should not be taken lightly by the uninitiated. The life-giving properties of the Stone, its necessity for the birth of the perfect metal and the development of the perfect soul had to be concealed. Therefore, the alchemical process of what was referred to as the Great Work was presented allegorically through planetary signs intermingled with cryptic language and symbols. This is where the egg comes back into play. Medieval alchemists embraced the beliefs of earlier Greek alchemists:

…It has been said that the egg is composed of four elements, because it is the image of the world and contains in itself the four elements ...

The egg has been called the seed and its shell the skin, its white and its yellow the flesh its oily part, the Soul, its aqueous part the breath or the air…12

The egg was considered as a symbol of the round universe, which could bring people into touch with the soul of the world. Due to this, the processes of the Great Work were carried out into the Philosopher’s Egg, also referred to as the Hermetic vase.

In alchemy, both man and metal had to undergo torture before they could be transformed and revived. This torture resulted in a death – the essential element in the process of resurrection. The principal idea of this was the redemption of humanity. Sound familiar? Take a look at this passage by medieval alchemist Basil Valentine:

Dear Christian amateur of the blessed art, oh! how the Holy Trinity has created the Philosopher's Stone in a brilliant and marvellous manner! For God the Father is a Spirit, and He appeared, however, under the form of a man, as is told in Genesis; in the same way we ought to regard the Philosopher's Mercury as a body spirit.

Of God the Father is born Jesus Christ, the Son, Who is at the same time man and God, and without sin. He had no need to die; but He died voluntarily, and rose again to make us live eternally with Him as His brethren without sin. Thus gold is without stain, fixed, glorious, and able to undergo all tests; but it dies for its imperfect and sick brethren; and soon, rising glorious, it delivers them, and colours them for life eternal; it renders them perfect in the state of pure gold 13

In this dramatic spectacle of suffering metals, of life, death, and resurrection, we must not forget the importance of consummation. Alchemical illustrations and texts expressed the union of sulphur and mercury as a marriage, an Alchemical Wedding, between the Sun (sulphur, king, father) and the Moon (mercury, queen, mother). In this sense, the ultimate goal of alchemy was the unification of masculine and feminine properties, which form within the egg.

The fascination with alchemy was recurrent among the surrealists. Its rich symbolism and its potential as a quest for self-knowledge was especially alluring. While the alchemist gains wisdom through the composition of materials used to create the Philosopher’s Stone, the surrealist does so by liberating the imagination. 14

We see this in Salvador Dalí’s Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937). The painting was conceived with Ovid’s Metamorphoses in mind. On the canvas we see Narcissus’ head metamorphosed into an egg held by a hand. In alchemy, the egg is an ideal, well-balanced form and microcosm, within its shell is where creation takes place. When it appears in works by Dali, its primordial character is ever-present, as envisioned by the artist:

I was able to see a pair of eggs... as if in hallucination. Then the eggs became innumerable and turned into a of soft white easy-to-handle substance, that I shaped somewhat as a baker would knead his dough. I felt that was at the source of power, in the cave of the great secrets. I was back in a kind of warm protective paradise, the essence of raw sensual enjoyment. 15

As we have learned, this vision of the egg was born out of creation myths and then re-interpreted for alchemical purposes. Like his peers, Dalí was no exception in his interest in alchemy, he expressed this openly :

The Catalan philosopher Raymond Lully an alchemist... inspires me. Like him, I believe in the transmutation of bodies. 16

Dalí is driven by the desire to portray his own character in his art by using elements of alchemy and mythology to express the obsessions of his life and place himself as a creator at the centre of the creative cycle. 17 While he interpreted alchemical symbolism to fit his own worldview, this consideration of alchemy was common - on alchemy and Surrealism, the movement’s founder, André Breton argues:

There is a remarkable analogy, insofar as their goals are concerned between the Surrealist efforts and those of the alchemists: the philosopher's stone is nothing more or less than that which was to enable man's imagination to take a stunning revenge on all things... after centuries of the mind's domestication.... [there is an] attempt to liberate once and for all the imagination. 18

As you consider the domestication of the mind and man’s imagination, you might find yourself wondering - what about the women?

Leonora Carrington was nineteen when she read her first books on alchemy while studying painting under Amédée Ozenfant in London in 1936. Under Ozenfant, she learned not just technique, but discipline:

You had to know the chemistry of everything you used, including the pencil and the paper. He would give you one apple, one bit of paper, and one pencil, like a 9H, which was like drawing with a bit of steel. And you had to do a line drawing, with one line. I was drawing the apple for six months, the same apple, which had become a kind of mummy. 19

This knowledge of materials led her to an important discovery – painting had a formula, a recipe. For Carrington, the amalgamation of cooking and painting equated to the purest form of alchemy.

Alchemy manifests on her canvases in two ways – on the one hand, Carrington’s characters regularly practice it in their magical activities, which often take place in kitchen, gardens, and dining rooms; on the other hand, Carrington performed her own form of magical cooking in the actual process of painting. By mixing egg yolks with her paints, her works attained the jewel-like tonalities of medieval and Early Renaissance panels, whilst allowing for association between painting and the process of cooking. It has also been suggested that the colour scheme used by Carrington in some of her works, like The Giantess, is alchemical as it encapsulates the three stages of transmutation: nigredo, albedo and rubedo. 20

Carrington was not alone in her experiments. In Mexico, the painter Remedios Varo became her soulmate in magic and art:

By using cooking as a metaphor for hermetic pursuits they (Carrington & Varo) established an association between women’s traditional roles and magical acts of transformation. They had both been interested in the occult, stimulated by the surrealist belief in the ‘occultation of the Marvelous’ and by wide reading in witchcraft, alchemy, sorcery, Tarot and magic. 21

Together, they developed their ideas on the alchemical kitchen as a magically charged domestic space, an idea that was not articulated by the male surrealists, despite their interest in alchemy.

From the very foundation of Surrealism, femininity was associated with irrationality, by implementing the occult to the movement, this attitude was somewhat transformed, and women were seen not just as femme enfants, but as sorceresses. This made magic in itself gendered – the male magus, the poet seer, and his counterpart – the woman as an otherworldly creature and enchantress. What this allowed was the inclusion of alchemy as a crucial philosophy in Surrealism, especially in its unification of the male and female through the Alchemical Wedding, but this put the woman in a supplementary position as opposed to an alchemist herself.

In their work, Varo and Carrington were reclaiming alchemy, which Bretonian Surrealism largely associated with male figures like Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim and Nicolas Flamel.

Eggs populate Leonora Carrington’s iconography as feminine symbols of power, we observe this in in her paintings, we read this in Down Below (1972), her harrowing recollection of her time spent in a psychiatric hospital:

This morning, the idea of the egg came again to my mind and I thought that I could use it as a crystal to look at Madrid in those days of July and August 1940—for why should it not enclose my own experiences as well as the past and future history of the Universe? The egg is the macrocosm and the microcosm, the dividing line between the Big and the Small which makes it impossible to see the whole. To possess a telescope without its other essential half—the microscope—seems to me a symbol of the darkest incomprehension. The task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope, while the left eye peers into the microscope. 22

Remedios Varo placed an emphasis on the power of women as creators. Within her work she used reproductive imagery – eggs, tubes, the womb – to refer not to reproduction but to the process of producing, of creation of self. 23

The painter Leonor Fini shared this point of view. She especially detested the male reading of the alchemical androgyne as a sexual act in which the male dominates. Fini, Varo and Carrington viewed painting as the ultimate creative act in which women are both autonomous and independent creators in terms of both art and reproduction:

In the art of Fini and Varo, this procreative ability is depicted somewhat differently to the accepted norm. Instead of the reproductive partnership between man and woman, in their art it is woman alone who is responsible for creation.

This removes their procreative women from the patriarchal sphere whereby women with children are simply housewives and nursemaids, reliant on their husband’s income. The women portrayed in the paintings of Fini and Varo are independent beings, whose ability to create new life also acts as a reference to the autonomy of the woman artist and her ability to create art. 24

Carrington, Varo and Fini asserted themselves as alchemists and magicians in their own right. Their work, which, happily, has been gaining more and more recognition, invites a new form of revolution within Surrealism, and art history as a whole.

And at the centre of it all, lies the egg.

I hope you have enjoyed learning about the history of the egg as a symbol of creation, resurrection, and transformation. Whether you celebrate Easter by paintings eggs, consuming large amounts of chocolate, or if you don’t celebrate at all, I’m grateful that you have made my words a part of your day. I hope the coming of Spring has brought forth a sense of renewal and awakening.

If you are someone who is interested in learning more about painting and literature through the prism of magic and folklore, please consider subscribing to this newsletter and followings its visual companion.

Thank you for reading.

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bibliography

Brandon, S. G. F. Creation Legends of the Ancient Near East. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1963.

Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Carrington, Leonora. Down Below. New York: New York Review Books, 2017.

Dalí, Salvador. The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dalí. Translated by H.J. Salemson. London: Quartet Books, 1977.

De Angelis, Paul, Whitney Chadwick, Leonora Carrington, and Patricia Draher. Leonora Carrington The Mexican Years 1943-1985. San Francisco: The Mexican Museum, 1991.

Ferguson, George. Signs and Symbols in Christian Art. New York: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Grew, Rachel. ‘The Use and Significance of Alchemy in the Works of Remedios Varo and Leonor Fini’. MPhil, University of Glasgow, 2006.

Haynes, Deborah J. ‘The Art of Remedios Varo: Issues of Gender Ambiguity and Religious Meaning’. Woman’s Art Journal 16, no. 1 (1995): 26–32.

Heyd, Milly. ‘Dali’s “Metamorphosis of Narcissus” Reconsidered’. Artibus et Historiae 5, no. 10 (1984): 212–131.

Kaplan, Janet. Unexpected Journey: The Art and Life of Remedios Varo. London: Virago, 1988.

Mercer, John Edward. Alchemy, Its Science and Romance. London: The Macmillan Company, 1921.

Newall, Venetia. ‘Easter Eggs: Symbols of Life and Renewal’. Folklore 95, no. 1 (1984): 21–29.

Newall, Venetia. ‘Easter Eggs’. The Journal of American Folklore 80, no. 315 (1967): 3–32.

Petrie, Tasmin. ‘The Revival of the Witch as Muse’. The Debutante (blog), 2020.

Radford, M.A. The Encyclopedia of Superstitions. Edited by Christina Hole. London: Hutchinson of London, 1961.

Ragai, Jehane. ‘The Philosopher’s Stone: Alchemy and Chemistry’. Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 12 (1992): 58–77.

Read, John. Prelude to Chemistry. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1937.

Stillman, John Maxson. Story of Alchemy and Early Chemistry. New York: Dover Publications, 1960.

S. G. F. Brandon, Creation Legends of the Ancient Near East (London: Hodder and Stoughton), 44.

Venetia Newall, ‘Easter Eggs’, The Journal of American Folklore 80, no. 315 (1967), 9.

Newall, Easter Eggs: Symbols of Life and Renewal’, Folklore 95, no. 1 (1984), 27.

M.A. Radford, The Encyclopedia of Superstitions, ed. Christina Hole (London: Hutchinson of London, 1961).

George Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 1959).

Newall, Easter Eggs, 21.

Newall, Easter Eggs, 24.

Jehane Ragai, ‘The Philosopher’s Stone: Alchemy and Chemistry’, Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 12 (1992), 58.

John Read, Prelude to Chemistry (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1937), 129.

Ragai, The Philosopher’s Stone, 59.

Ragai, The Philosopher’s Stone, 60.

John Maxson Stillman, Story of Alchemy and Early Chemistry (New York: Dover Publications, 1960), 171.

John Edward Mercer, Alchemy, Its Science and Romance (London: The Macmillan Company, 1921), 146.

Milly Heyd. ‘Dali’s “Metamorphosis of Narcissus” Reconsidered’. Artibus et Historiae 5, no. 10 (1984), 122.

Salvador Dalí, The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dalí, trans. H.J. Salemson (London: Quartet Books, 1977), 136.

Dalí, The Unspeakable Confessions, 147.

Heyd, Dali’s “Metamorphosis of Narcissus” Reconsidered’, 131.

André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972), 178.

Paul De Angelis et al., Leonora Carrington: The Mexican Years 1943-1985 (San Francisco: The Mexican Museum, 1991), 34.

Tasmin Petrie, ‘The Revival of the Witch as Muse’, The Debutante (blog), 2020.

Janet Kaplan, Unexpected Journeys: The Art and Life of Remedios Varo (Virago, 2022), 95.

Leonora Carrington, Down Below (New York: New York Review Books, 2017), 37.

Deborah J. Haynes, ‘The Art of Remedios Varo: Issues of Gender Ambiguity and Religious Meaning’, Woman’s Art Journal 16, no. 1 (1995), 31.

Rachel Grew, ‘The Use and Significance of Alchemy in the Works of Remedios Varo and Leonor Fini’ (MPhil, Glasgow, University of Glasgow, 2006).

💐 belated thank you 🙏🏽

Really interesting read - thank you!