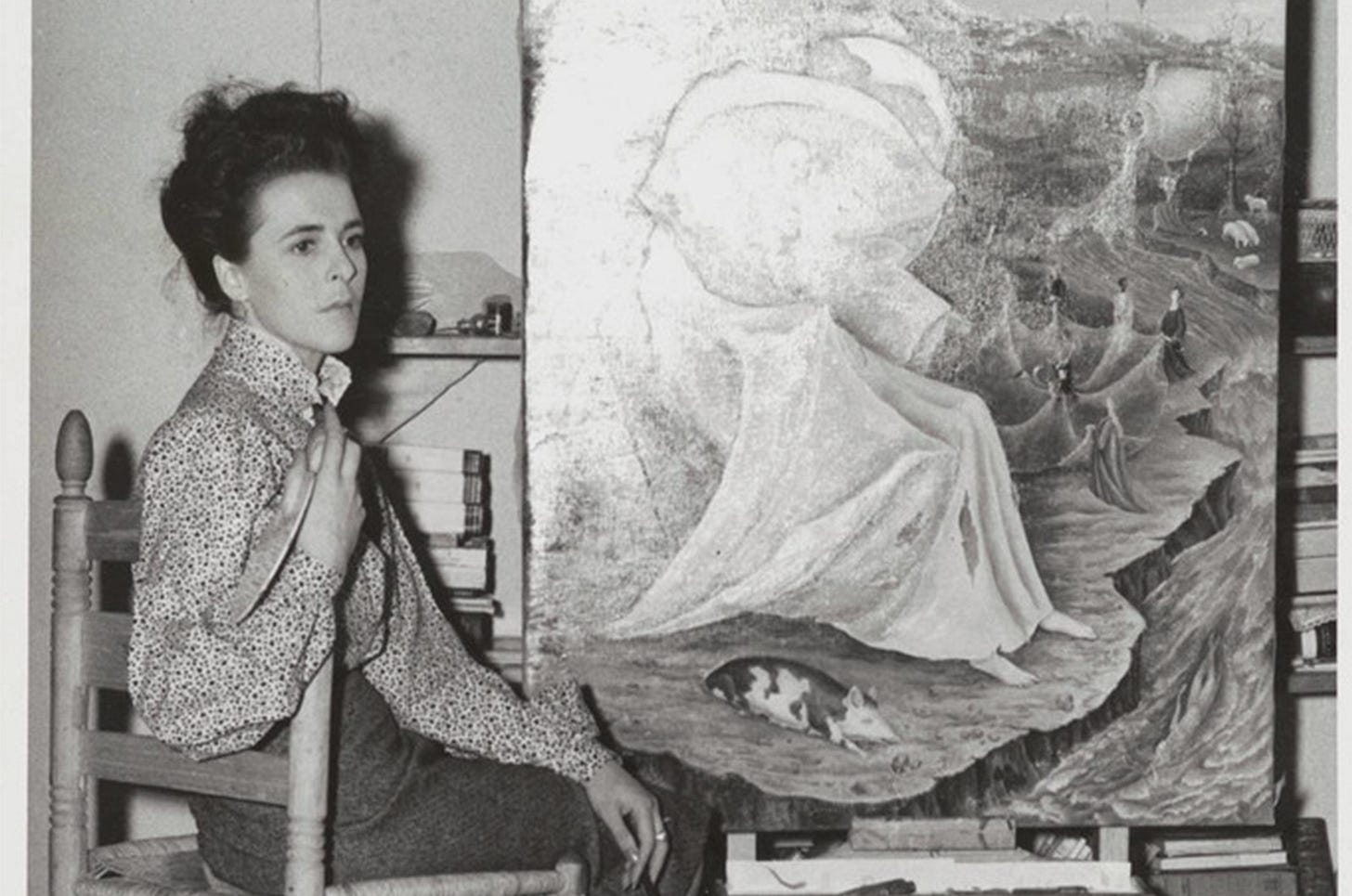

A cauldron bubbling under the watchful eyes of a giant goose, dinner tables rich with wine and fruit, the daughter of the Minotaur and her loyal hounds. These are some of the fantastical scenes one can find in the paintings of Leonora Carrington. Her striking characters, as charming as they are bizarre, are eternally engaged in magical activity on canvases that come to life through the tragic and comedic engaged in a Bacchanalian dance.

Dear coven, today I want to introduce you to my favourite artist and the reason why I pursued my studies in the first place.

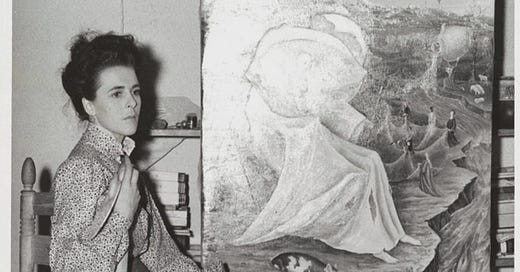

Leonora Carrington was an artist who searched for meaning in the occult, in Buddhism, in Spiritualism, in fairy tales and fables. 1 Born in 1917 in South Lancashire, Carrington’s life was filled with dramatic intensity, and her work rests somewhere between the real and the imagined.

Magic was unveiled to her in childhood, through the stories told by her grandmother and Irish nanny. Her Catholic upbringing was infused with tales of witches and faeries, and the Tuatha Dé Danann. Carrington saw ghosts haunting the eerie corridors of her childhood home, Crookhey Hall, but it was the suffocation of debutante dresses and the allure of rebellion that made her flee her family. In 1937, she abandoned family wealth and marriage prospects for Paris, Max Ernst and a group of like-minded individuals gathered in corner cafes. That is how Carrington entered Surrealism.

Despite her affiliation with the group, Carrington did not entirely fit in. She was beautiful and clever – two qualities of extreme importance to the male surrealists. However, while her work was respected, the focus remained on her persona.

The founder of Surrealism, André Breton, described her as such:

Who so beautifully did justice to the Witch, highlights among her gifts two that are invaluable, because granted only to women: “the illuminism of lucid madness” and the “sublime power of solitary conception”

…Who totally could answer that description better than Leonora Carrington? 2

While her lover, Max Ernst, was classified as a Magus artist, Carrington’s magic was especially appreciated for its ‘womanly’ qualities. A rebel since birth, she subverted each trope aimed her way.

Carrington is the subject of my Doctoral thesis, so you can imagine I have quite a bit to say about this (three hundred pages worth of things to say, in fact, hopefully coming soon in a bookstore near you). For now, though, let us focus on the one trope that plagues most women involved with a predominantly male movement – the Muse.

At this point, are we shocked that any woman who falls in love with an artist (or vice versa) must become his muse? Unfortunately, no, not even today, and even more so, not in the late 1930s. Surrealism is especially problematic in this – from its very conception femininity was associated with a much-desired irrationality. That being said, this concept is not new, and it certainly wasn’t then, as ideas of this kind can be traced throughout the history of art:

No male artists, however gifted he may be, will ever be able to experience all the emotional life to which women are subject.

And no woman of abilities…will be able to borrow from men anything so invaluable to art as her own intuition and the prescient tenderness and grace of her nursery-nature. 3

While Surrealism was not solitary in its perception of the woman as an intuitive and tender creature, it is within the movement that Carrington was cast as a Muse. Carrington confronted this label head-on through her representation of the self.

At this point, most would turn to Carrington’s self-portrait. And they should, I have done the same in my thesis. The self-portrait is a wonderful example of Carrington’s writing and painting crossing over with its reference to her story The Debutante, it also demonstrates her subversion of gender roles, and her placement and displacement of symbols. Most of all, it is a powerful assertion of the self as a painter, a rite of passage for women in Surrealism (take a look at Leonor Fini, Dorothea Tanning Eileen Agar and Valentine Hugo who were all particularly drawn to portraiture as a mode of expression). 4 However, today I want to underscore one of my favourite motifs Carrington used to discard the label of the Muse – the crone.

The image of the crone has its roots in folklore, medieval and Renaissance art and literature. I am planning a deep dive on this exact history of representation, so stay tuned. For now though, I will introduce you to how Carrington’s commandeered the trope through her novel The Hearing Trumpet (1974). As recounted by Whitney Chadwick, aging had occupied Carrington’s thoughts as she considered how she will live for the rest of her life:

Focusing on the image of the crone, the ancient woman; she has rejected the ideals of youth and beauty that dominate both contemporary culture and most of the history of western painting. The painting of aged and wrinkled faces – along with the restoration of knowledge and power to the elderly – are perfect in keeping with Carrington’s belief that unless women reclaim their power to affect the course of human life, there is little hope for civilization. 5

This type of thinking is what resulted in Carrington writing The Hearing Trumpet, a novel with a curious titular character - Marian Leatherby, an old lady who dreams of Lapland. Why? In her own words: because the shamans of Lapland just happen to be the most magical people on Earth. 6

The ninety-two-year-old woman’s humanity is non-existent to those around her, as we note from the discussion she hears between her family concerning her admission to a home:

‘We are not in England,’ said Galahad. ‘Institutions here are not fit for human beings.’

‘Grandmother, said Robert, ‘can hardly be classified as a human being. She is a drooling sack of decomposing flesh.’

‘Remember Galahad,’ added Muriel, ‘these old people do not have feelings like you or I.’ 7

Marian does end up in a home, she finds herself in a place that ‘creeps with ovaries’, ovaries found in the bodies of ‘bald and bearded crones’. 8 Lightsome Hall, run by Dr. Gambit, parodies George Gurdjieff and offers a new and esoteric Christian path to self-discovery, but Marian is uninterested. Instead, she discovers another world beneath Dr. Gambit’s regime, as she is given ancient texts on Dona Rosalina, the Abbess of the Convent of Santa Barbara de Tartarus.

The Abbess makes herbal remedies and plays with unbaptised children, she seeks ultimate knowledge, and she is liberated. She is patriarchy’s walking nightmare.

From this point, the novel follows several pursuits of the Holy Grail – Dona Rosalinda’s mysterious quest; Marian’s own search; and a group of old ladies, poets and animals. Pointedly, the male characters of this quest are caught up in the Christian version of the story of the Holy Grail, while the women belong to an earlier, matriarchal view of the myth. 9

The Celtic influence is evident in Carrington’s re-telling of the Grail stories:

He let me understand that the Knights Templar in Ireland were in possession of the Grail. This wonderful cup, as you know, was said to be the original chalice which held elixir of life and belong to the Goddess Venus…The story follows that Venus, in her birth pangs, dropped the cup and it came hurtling to earth, where it was buried in a deep cavern, abode of Epona the Horse Goddess. 10

Carrington’s novel challenges women’s roles in society; religious dogmas; and humans’ relationship with nature.

At the start of her journey, Marian falls down a cauldron, the alchemist’s oven, and what is considered a Celtic symbol for the Holy Grail. When Marian’s quest is at its end, the crones forge alliances with animals and mythological creatures to reclaim the Grail from the male figures in the story.

At the end of the book, Marian and her band of old ladies hope that the current state of the planet - peopled with cats, werewolves, bees and goats – will bring about ‘improvement on humanity, which deliberately renounced the Pneuma of the Goddess’. 11

Marian’s journey is ultimately set afoot within the kitchen space, her findings and her liberation, all point to the alchemical discoveries Carrington hoped to attain through her own work. It is important to recognise that while Carrington sought to dominate the domestic role assigned to women in the kitchen and to transform the room into a magical space, she did not aim to take away its comfort and safety. Within Lightsome Hall, the kitchen is a magical circle, but it is also a space where fudges and biscuits are made.

Carrington’s persistent sense of humour makes the bizzarreness of her work easier to digest, and, after all, what is a crone without her resounding cackle?

If you want to join Marian and her merry band of crones on their adventure, do read The Hearing Trumpet, it’s a brilliant, magical novel that paints a wonderful portrait of who Leonora Carrington was as a person and a writer.

I hope you enjoyed this little introduction to Leonora Carrington. Every month, I will be writing about modernist artists influenced by magic. If you wish to learn more, join the coven by subscribing to this newsletter and following its visual companion.

Thank you for reading.

bibliography

Aberth, Susan. Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art. London: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, 2010.

Breton, André. Anthology of Black Humour. San Francisco: City Light Publishers, 2001.

Byatt, Helen. ‘Introduction’. In The Hearing Trumpet. Boston: Exact Change, 1996.

Carrington, Leonora. The Hearing Trumpet. Boston: Exact Change, 1996.

Chadwick, Whitney. Leonora Carrington - Recent Works. New York: Brewster Gallery, 1988.

Meskimmon, Marsha. The Art of Reflection: Women Artists’ Self-Portraiture in the Twentieth Century. London: Scarlet Press, 1996.

Orenstein, Gloria. ‘Art History and the Case for the Women of Surrealism’. The Journal of General Education 27, no. 1 (1975): 31–54.

Orenstein, Gloria. ‘The “Problematics” of Writing about Sacred Ritual and the Spiritual Journey’. Women’s Studies Quarterly 21, no. 1/2 (1993): 22–37.

Susan Aberth, Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art (London: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, 2010), 8.

André Breton, Anthology of Black Humour (San Francisco: City Light Publishers, 2001), 335.

Walter Sparrow in Gloria Orenstein, ‘Art History and the Case for the Women of Surrealism’, The Journal of General Education 27, no. 1 (1975), 33.

Rosy Martin in Marsha Meskimmon, The Art of Reflection: Women Artists’ Self-Portraiture in the Twentieth Century (London: Scarlet Press, 1996), xv.

Whitney Chadwick, Leonora Carrington - Recent Works (New York: Brewster Gallery, 1988), 4.

Orenstein, The "Problematics" of Writing about Sacred Ritual and the Spiritual Journey, 31.

Carrington, The Hearing Trumpet, 15.

Carrington, The Hearing Trumpet, 42.

Helen Byatt, ‘Introduction’, in The Hearing Trumpet (Boston: Exact Change, 1996), 15.

Carrington, The Hearing Trumpet, 115.

Carrington, The Hearing Trumpet, 199.

Have been meaning to read Carrington since I learnt she was a friend of Barbara Comyns, of whom I'm a great fan. Will try and track down a copy of The Hearing Trumpet soon!

This is a great piece! What an interesting life and take on the world. I love learning about amazing historical woman :)