Dear coven,

For this week’s enchantment I would like to introduce you to the work of Ithell Colquhoun. For those new here, enchantment of the week is a weekly series in which I introduce you to painting, photography, literature, and various works of art that were motivated by magic. Let’s begin.

Ithell Colquhoun was always fascinated by the occult. Not just an artist, but a practising occultist, she found expression through heterodox spirituality. Colquhoun began investigating the esoteric far before encountering Surrealism. In the mid-1920s, while attending Cheltenham Ladies College her interest in alchemy was sparked and she dove deep into any and all alchemical texts that she could get her hands on. What provoked this curiosity was a newspaper article on Aliester Crawley’s Abbey of Thelema and the early essays of W.B. Yeats. 1

This call for the esoteric persisted, in 1928 while studying at the Slade School of Art in London, she became a member of the Quest Society, an occult group with theosophical underpinnings. 2

Colquhoun was introduced to Surrealism in 1931 when she stayed in Paris, but it was a lecture by Salvador Dali that attracted her to the movement. Unfortunately, the surrealists were not as welcoming as she had hoped. The London surrealist group had strict rules and forbade its members to participate in any secret society or publish anywhere outside the auspices of the surrealist movement. 3 Colquhoun rejected these restrictions, especially where pursuing the occult was concerned:

I wished to be free to continue my studies in occultism as I saw fit. 4

While this led to her expulsion from the group, she remained committed to the surrealist approach of painting and writing in her own work.

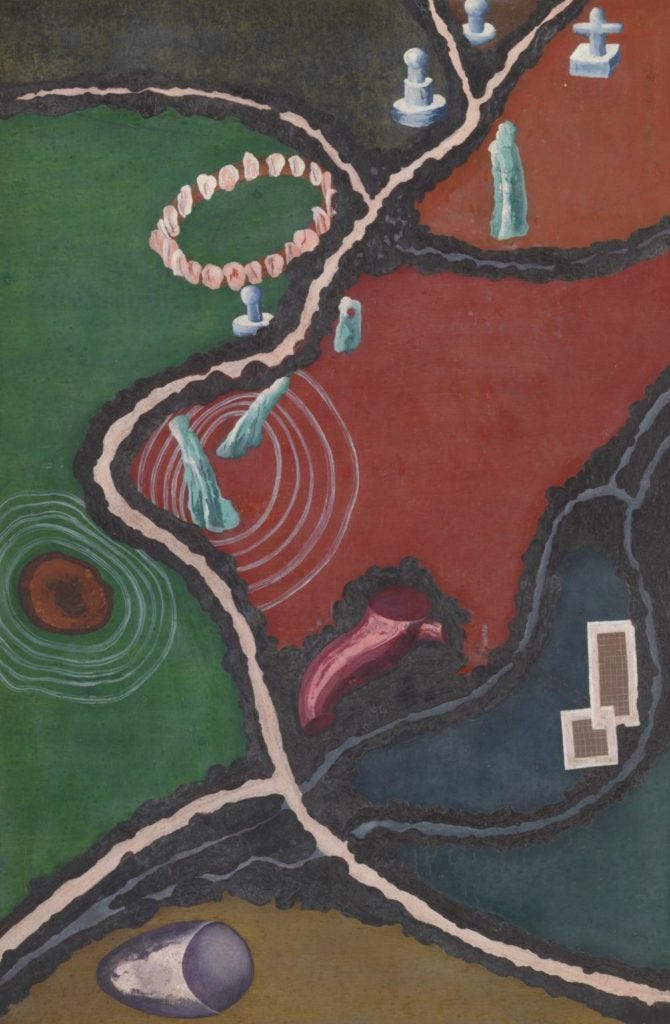

She was especially enamoured with techniques such as automatism, remarking on its magical quality when regarding her text ‘The Mantic Stain’, in her words:

The Mantic Stain drew parallels between the treasury of ‘mindpictures’ brought up by surrealist automatic methods and the imaginative interpretations involved in divinatory practices and alchemical transformation. 5

We can note her alignment with surrealist ideas on dreams from her comments on her painting:

I learnt to draw at the Slade School. I have not yet learnt to paint. I am teaching myself to carve and to write. Sometimes I copy nature, sometimes imaginations, they are equally useful. My life is uneventful but I sometimes have an interesting dream. 6

Her exclusion from exhibitions and gatherings pushed her to act independently, a challenge she was more than willing to accept.

Her occult knowledge supplemented her art and writing, and her familiarity with the theories and philosophies of alchemy, Rosicrucianism, Gnosticism, Tarot, Christian Mysticism and Celtic lore becomes evident in the biography she wrote for MacGregor Mathers, one of the leaders of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

While her membership for the Order was rejected she did join Aliester Crowley’s Ordo Templi Orientis and Kenneth Grant’s New Isis Lodge. She participated in rituals within the Druid Order, was a member of several Masonic Lodges, became a deaconess of the Ancient Celtic Church and was a Priestess of Isis in the Fellowship of Isis. 7

In 1959 Colquhoun left London and moved to Cornwall permanently where she continued to explore divine feminine power as a path for social transformation. She found endless inspiration in Cornwall’s folklore, its spirituality and neolithic landscape. On the move to Cornwall:

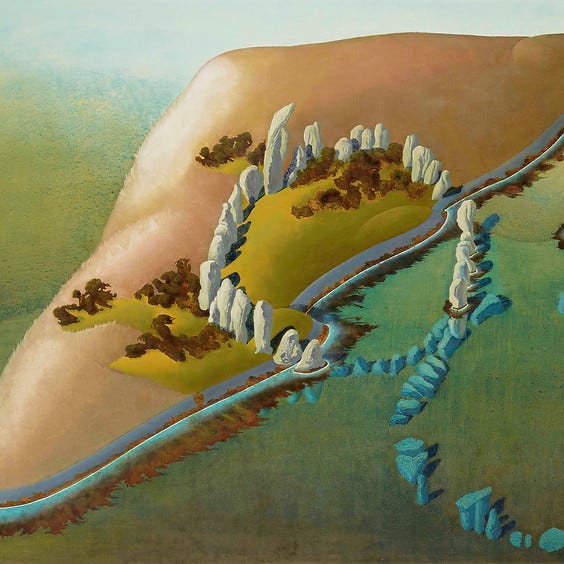

In Cornwall her understanding of the world as a connected spiritual cosmos led her to deepen her creative explorations inspired by the region’s ancient landscape, Celtic mythologies, and neolithic monuments. 8

She hired a studio near Lamorna, named Vow Cave, with no water or electricity, but with a rich deposit of weathered stone crosses and stone circles. Colquhoun delved deeper into Celtic mythology and wrote a handbook on the county. She sensed an energy in Cornwall that saw the standing stones as living beings:

Stones that whisper, stones that dance, that play on pipe or fiddle, that tremble at cockcrow, that eat and drink, stones that march as an army – these unhewn slabs of granite hold the secret of the county’s inner life. 9

Colquhoun’s journey into the surreal and the occult continued her entire life. For those able to visit London, Tate Britain is currently running an exhibition featuring Ithell Colquhoun’s work, it will be on until the 19th of October, so plenty of time to see it and definitely not one to miss if you can make it.

I hope you have enjoyed this little introduction to Ithell Colquhoun and her work. If you are interested in learning about more artists and works of art and literature that deal with magic and surreality, consider subscribing to this newsletter.

Thank you for reading.

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

Ithell Colquhoun, Sword of Wisdom: MacGregor Mathers and the Golden Dawn, Neville Spearman, London, 1975, 15-6.)

Victoria Ferentinou, ‘Ithell Colquhoun, Surrealism and the Occult’, Papers of Surrealism, no. 9 (2011): 1

Paul C. Ray, The Surrealist Movement in England, Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London, 1971, 228: Remy, Surrealism in Britain, 210-1, 226

Ithell Colquhoun, Surrealism: Paintings, Drawings, Collages 1936-76

Ithell Colquhoun, ‘The Mantic Stain,’ Enquiry, Vol. 2, No. 4, October-November 1949, 15-21

Dawn Ades, ‘Notes on Two Women Surrealist Painters: Eileen Agar and Ithell Colquhoun’, Women in Art 3, no. 1 (1980): 39

Victoria Ferentinou, ‘Ithell Colquhoun, Surrealism and the Occult’, Papers of Surrealism, no. 9 (2011): 4

mboi

https://www.travellerintheevening.com/p/ithell-colquhoun-mantic-stains