Dear coven,

Welcome to enchantment of the week, a weekly series in which I discuss works of art motivated by magic. For this week’s enchantment, I want to introduce you to the text Down Below by Leonora Carrington.

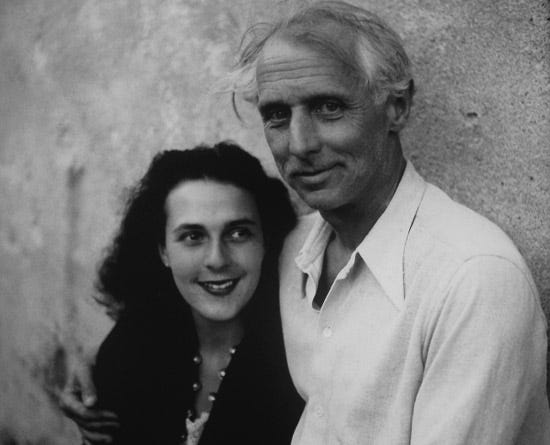

At 23 years old Leonora Carrington became alone in this world. At the outbreak of war, her lover, Max Ernst, was detained by the authorities, her family had disowned her, and the surrealists were fleeing France.

With the dangers of an approaching war and the loneliness at St Marin d’Ardeche, it is no surprise Carrington lost her grip on reality. Her emotional state at the time drove her to delusions, periodic fasting, performing hard physical labour in their gardens, and forcing herself to vomit.

Near the end of June 1940, Catherine Yarrow, an old British friend, visited Carrington with her husband Michel Lukas. They were both alarmed by the artist’s erratic behaviour, so they convinced her to come with them to Spain, where they were hoping to secure a visa for Ernst in Madrid. However, her growing anxiety and delusional culminated in an episode that got her apprehended by the police and subsequently sent to a mental asylum in Santander.

Carrington was diagnosed as psychotic and was given Cardiazol treatments – a drug that caused spasms, similar to electric shock therapy. At that point, for the first time in her life, Carrington felt that she was vulnerable:

I suddenly became aware that I was both mortal and touchable and that I could be destroyed. I didn’t think so before. 1

It took Carrington two years after she was admitted to illustrate her experience and when she did she began displaying the signs of mythmaking and world building that would strongly define her writing and art in later years. Gloria Orenstein has referred to this period not as a breakdown, but as a breakthrough, as Carrington herself saw the fictional place dubbed ‘Down Below’ as a space of self-discovery. During her time in Santander, she reconfirmed the injustices in the world that she felt the need to tackle and used her pen and paintbrush as weapons for her vindication.

Her harrowing experience is detailed in her text Down Below (1944), which serves as a transcript and a peek into the instability of her mind at the time. She described how she felt like an animal, strapped down, beaten, silenced. But she also found a power within herself –

I felt that through the agency of the Sun, I was an androgyne, the Moon, the Holy Ghost, a gypsy, an acrobat, Leonora Carrington, and a woman. 2

In her recollection of madness, Carrington, as a woman, reclaims her power over the universe, placing herself as an omnipotent goddess as she begins to regulate the conduct of the world as she names objects and their symbolic significance.

The objects in question all represent a part of the world – French coins are the downfall of men; a red and black pen represents intelligence; a box of Tabu powder that is half-grey and half-black represents the eclipse and vanity; her two jars of face cream each have their own meaning, the one with the black lid stands for the moon, for woman and destruction, the one with the green lid represents the Sun, construction, men; a nail buff is the journey into the Unknown and a protection talisman; a lipstick is art itself. When grouped together those items form a microcosm of her own creation, they represent the celestial path that made sense to her.

When she enters the Down Below she is not consumed by darkness, she has instead tapped into a mystical power. However, in her depiction Leonora Carrington steers clear of romanticising insanity, stating:

I was convulsed, pitiably hideous. 3

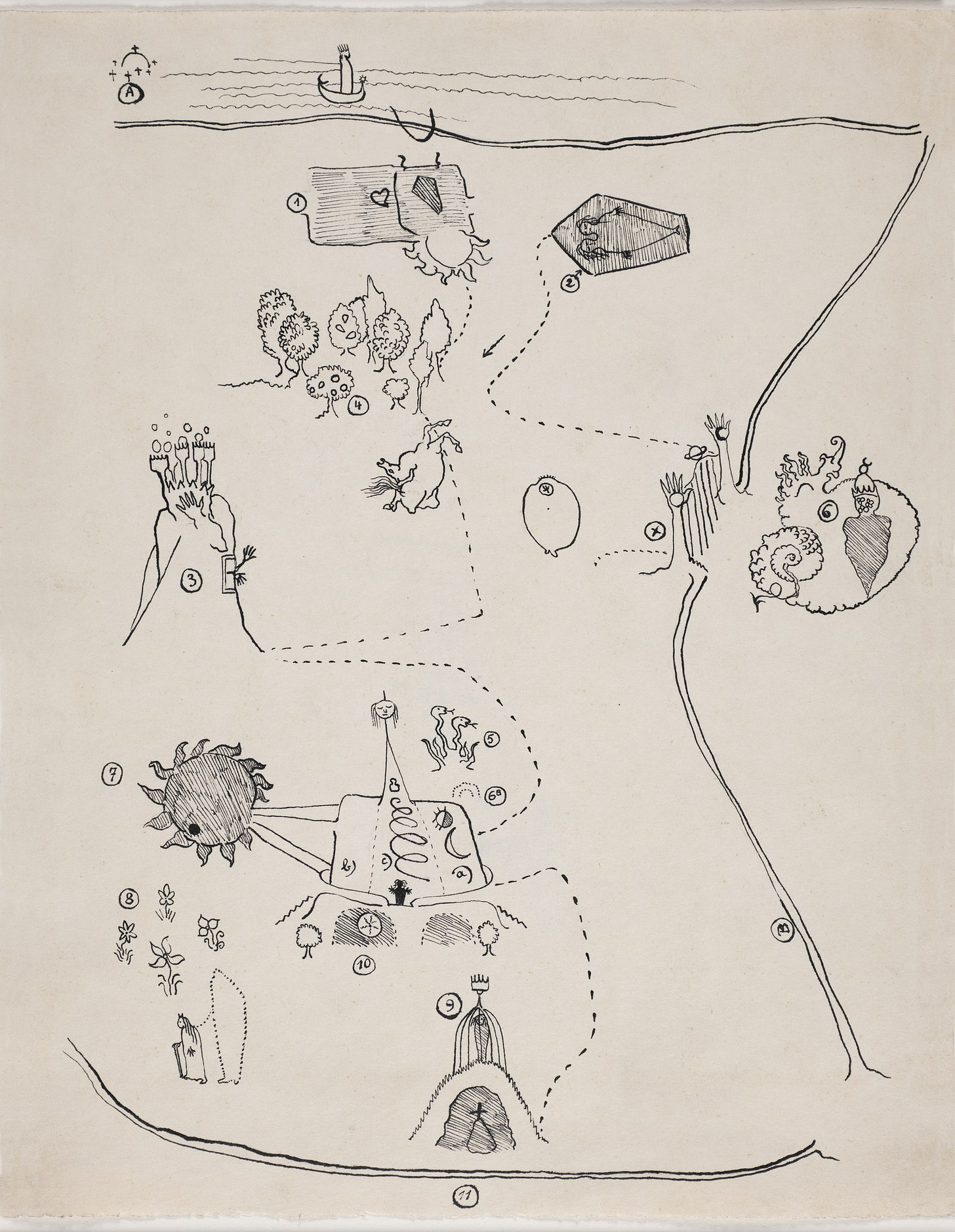

Despite the moments of striking realism, Carrington does not glorify, but instead mythicize her experience, presenting it as an expansion of her mind, an embrace of her power, as well as her weakness. Within Down Below Carrington looks to her past, present and future and with the use of familiar mystical symbols outlined a map of her mental state.

This morning, the idea of the egg came again to my mind and I thought that I could use it as a crystal to look at Madrid in those days of July and August 1940—for why should it not enclose my own experiences as well as the past and future history of the Universe?

The egg is the macrocosm and the microcosm, the dividing line between the Big and the Small which makes it impossible to see the whole. To possess a telescope without its other essential half—the microscope—seems to me a symbol of the darkest incomprehension. The task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope, while the left eye peers into the microscope. 4

The egg held an alchemical and magical significance to a vast number of surrealists, Carrington and a fair few of her female contemporaries applied its symbolism of fertility to their work in an act of reclaiming and subverting traditional femininity. For more on the egg, Surrealism, and alchemy, have a look here.

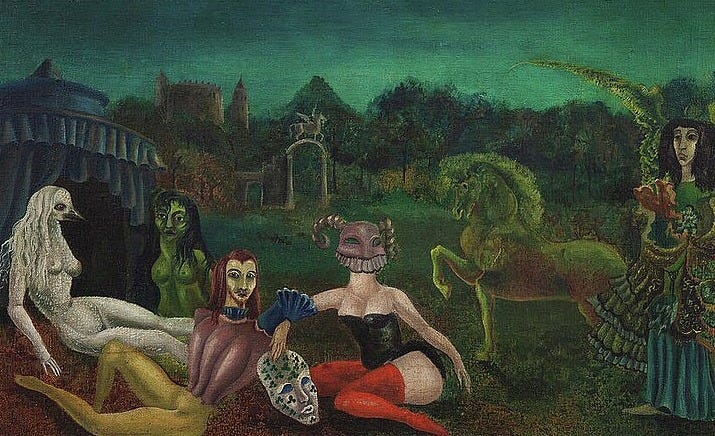

Sparking up trends she would continue to follow in her later painting and writing, Carrington cooks up a bubbling mixture of Catholicism, alchemy and magic and spills her cauldron onto the pages of Down Below. The textual narrative presents itself visually in her painting of the same title.

I hope you have enjoyed this introduction to Leonora Carrington’s Down Below. If you would like to learn more about works motivated by magic and Surrealism, consider subscribing to this newsletter and following its visual companion on Instagram.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

Leonora Carrington in the House of Fear, produced and directed by Kim Evans, 1992

Leonora Carrington. Down Below. New York: New York Review of Books, 2017, 53.

Carrington, Down Below, 51.

Carrington, Down Below, 37.

Thank you very much.

This made me realize I'm due for a re-read of Down Below. It's so concise but packs a lot of punch. I don't think I could take it all in on the first reading, but reading your article made me realize how skillfully Leonora revisited her psychotic break with so much lucidity.

One moment that really stuck with me from the book is how when Leonora was descending into "madness" wild animals were no longer afraid of her, and even approached her as one of their own. This seems to illustrate her state of mind not as complete irrationality, but as a different kind of consciousness that is equally valuable. The more that I reflect on this book the more important it seems to understanding "altered" states of consciousness