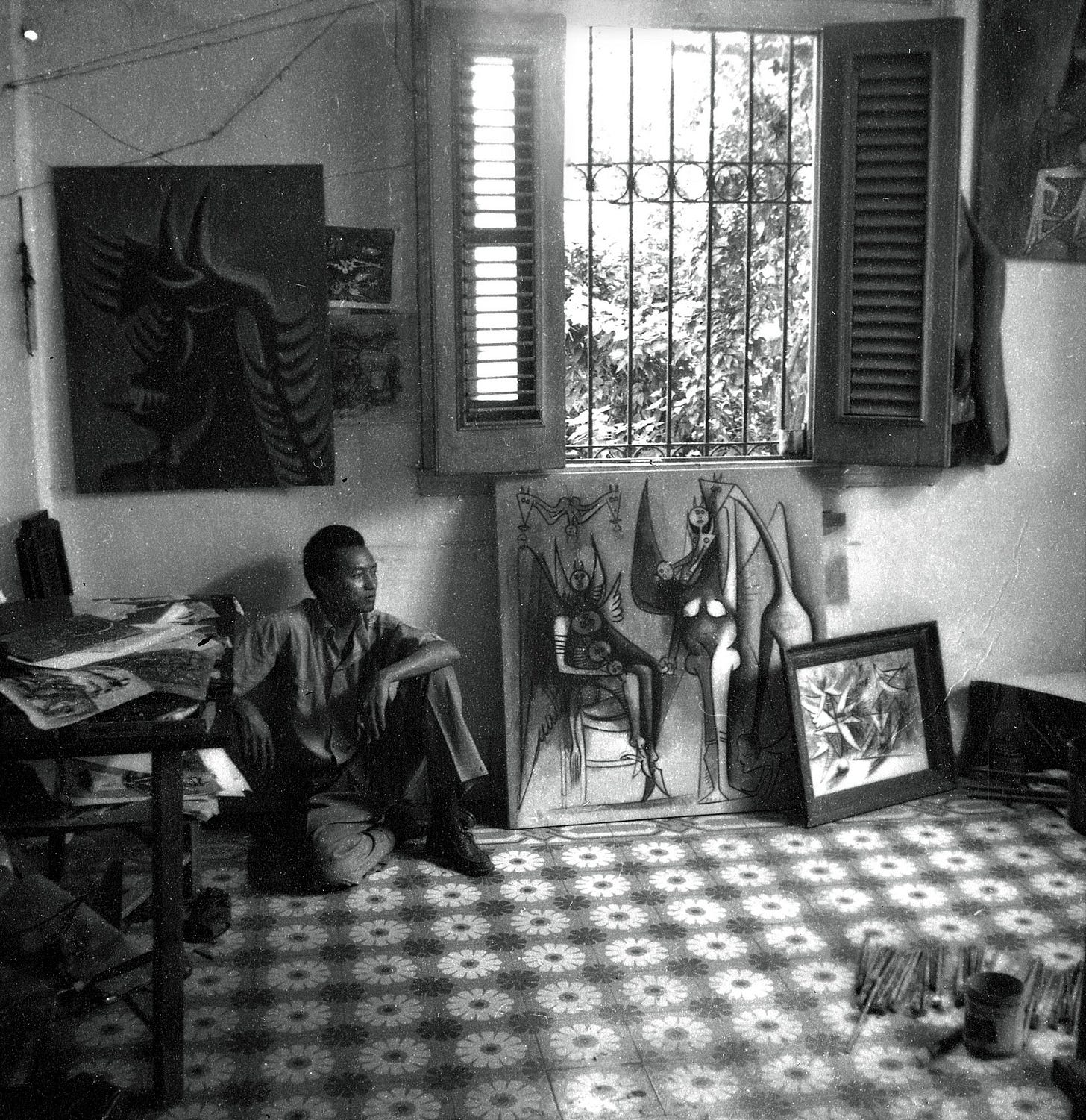

For this week’s enchantment I would like to introduce you to the work of Wifredo Lam. For those new here, enchantment of the week is a weekly series in which I introduce you to painting, photography, literature, and various works of art that were motivated by magic. Let’s get right into it.

Wifredo Lam travelled far and wide, his journey reflected in his drawings of Cuenca, his surrealist sketches in the 1930s, and his vibrant canvases which immerse you into jungles alive with magic. His experience within the surrealist group allowed him to both liberate and embrace his heritage alongside the formalism of Cubism and the invention of Surrealism. 1

Lam grew up in the sugar farming village of Sagua la Grande in Cuba, the son of a Cuban-Chinese immigrant father and a Conglese, formerly enslaved mother. His godmother, Matronica Wilson, was a Santería priestess, healer, and sorceress. It is from her that he first discovered the spiritual practices that would become instrumental to his work. 2

He studied in Madrid where he travelled the countryside and was eventually drafted to defend Madrid in the Spanish Civil War. In 1938 moved to Paris and soon found his way into the cubist and surrealist circles.

Lam was a part of the Parisian avant-garde in the 1940s, though he quickly left the city for Marseille as it was falling to the Vichy government. After Marseille, he fled for the Caribbean and he finally arrived in Havana in 1942. He later admitted that he went to Europe to escape Cuba, but despite his initial resistance he found his imagination was greatly by the country’s landscape and tradition.

In Havana, he was able to embrace his heritage away from the Parisian scene. While he was in Paris, Lam encountered the masks and ornaments of his ancestor, worshipped for their contribution to modern art, but to a large extent fetishised and in service of the Western view of ‘primitive’ art. Both Picasso and the founder of Surrealism, André Breton were greatly interested in Lam. While they were fascinated with his work, it cannot be overlooked that they found his race and what it means for his work especially appealing, seeing him as a symbol and token first and as an artist second.

Lam disrupted the manipulation of Cuban culture by foreign interests and instead positioned himself as an agent of cultural liberation from harmful Western influences. In a dialogue with his biographer, Lam stated:

I decided that my painting would never be the equivalent of that pseudo-Cuban music for nightclubs. I refused to paint cha-cha-cha. I wanted with all my heart to paint the drama of my country. In this way I could act as a Trojan horse that would spew forth hallucinating figures with the power to surprise, to disturb the dreams of the exploiters. 3

When Lam first returned to Cuba he was shocked at the racial inequality and corruption of his country, which is what provoked his exploration of Cuban culture, and in turn produced the vivid imagery on his canvases. Lam has described his painting as an act of decolonization, not in a physical, but in a mental state:

Africa has not only been dispossessed of many of its people, but also of its historical consciousness … I have tried to relocate Black cultural objects in terms of their own landscape and in relation to their own world. 4

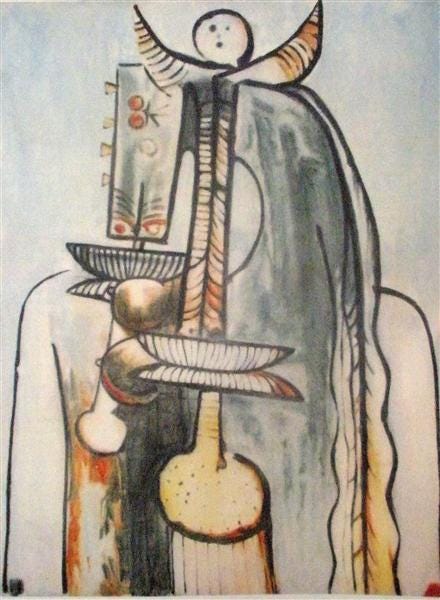

Lam found folklore and ritual especially appealing and he attended many Afro-Cuban religious rituals alongside ethnologist and folklorist Lydia Cabrera. He became fascinated with the Santería religion, which infused West African beliefs with aspects of Catholicism.

Lam was especially interested in the anthropomorphic deities of Afro-Cuban religion. In his response to Cuba’s broader history, geography and ecology, Lam developed his motif of a woman placed within a lush landscape. His invention of this culturally specific still-life composition referred directly to the devotional practices of the Lucumí religion. 5 Another persistent element is a femme cheval, a horse woman, we see her in his drawings of 1943, who signifies the deity Oya, the huntress.

Wifredo Lam’s work is crucial not just to the portrayal of magic and mythology in art, but for its fierce reclaiming of what was taken from his ancestry and culture. Lam did not reject Modernism, he instead de-centered it and expanded its reach globally:

Lam’s art mounts as an orisha on the horse of modernism, making it pronounce different words…It represents a decolonizing milestone in art, a breaking point of the Western meta-subject that ‘others’ de facto everything else. 6

I hope you have enjoyed this introduction to Wifredo Lam. If you are interested in learning about more artists and works of art and literature that deal with magic and surreality, consider subscribing to this newsletter and following its visual companion on Instagram.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

Lowery Stokes Sims, ‘The Painter’s Line: The Drawings of Wifredo Lam’, Master Drawings 40, no. 1 (2002): 62

Mario Fierro, "Wifredo Lam: Negotiating Transcultural Modernism and Artistic Identity in Europe, The Caribbean, and The United States" (2011), 61-62

Lowery Stokes Sims, ‘The Painter’s Line: The Drawings of Wifredo Lam’, 64.

Gerardo Mosquera, “Jineteando el modernismo. Los descentramientos de Wifredo Lam,” Lápiz 16, no. 138 (1997), 24.

Another artist worth acknowledging by exposition, research and well-presented journalism like yours. Thank you.

Thank you, such an interesting artist!