I felt myself to be a deer around dogs barking, and I created for myself another place. It is this other place that I occupy since then. 1

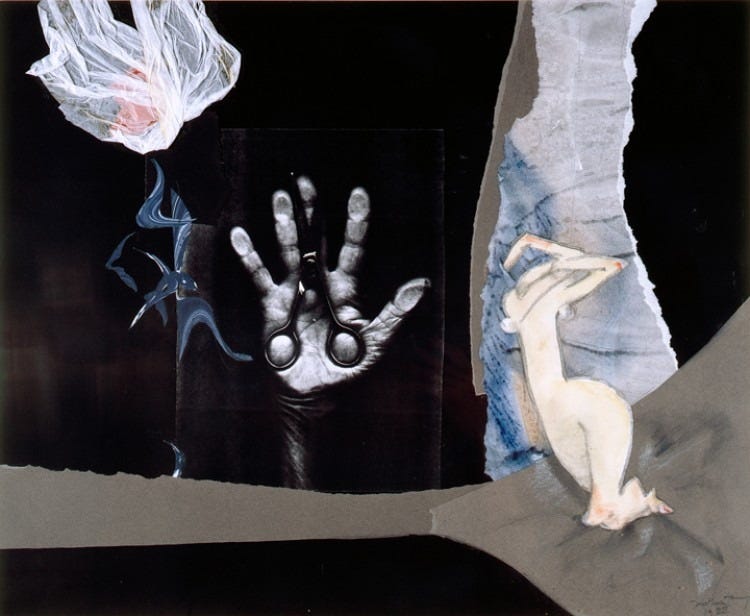

Dorothea Tanning denied that her art is autobiographical. Instead, she saw her work as an allegory of a dream state, a history of her dreams. From this history we can extrapolate a vision, one drenched in alchemy, populated by spirits, and one that holds the key to the endless corridors of doors we can spot in Tanning’s paintings.

Dorothea Tanning was born in 1910 in Galesburg, Illinois. As a child, she felt isolated, she longed for escape. She practiced her escapism in 1927, at the Galesburg Public Library, where she worked part-time. The librarian had marked a red cross against a number of books that were considered immoral and unfit for minors. This was convenient for Tanning, it made it easy to discover which books she absolutely had to read - Erewhon, Leaves of Grass, Salammbô, The Scarlet Letter, The Red Lily - treasures she called ‘delicious hymns to decadence’. 2 Perhaps it was there that Tanning discovered the Gothic literature that would motivate her paintings, such as Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), which she refers to in her painting A Mrs Radcliffe called today (1944). The painting features a plethora of gothic iconography - castle arches, ghostly figures, and an unreliable narrator.

In her work, Tanning deploys the language of drama, excess and irrational to evoke a certain gothic sensibility. 3 She arrived to Surrealism late in its trajectory, but this very sensibility made her well-prepared to enter the movement, which had harbored a fascination with both gothic and romantic literature.

The gothic novel first materialised with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), in the twentieth century, it made its way to the silver screen through films such as Les Vampires (1915) by Louis Feuillade and Nosferatu (1922). Studies, such as Edith Birkhead’s The Tale of Terror (1921), brought forth a revival of gothic literature when Surrealism was first emerging. Birkhead predicted that the rise of psychoanalysis would force a reexamination of the genre.

Surrealism, with its longing for dreams already shared the Gothic fascination with the nocturnal and the taboo:

At its best the Gothic novel embodies the triumph of the creative imagination in an all-consuming, obsessive pursuit of desire, providing in place of Surrealism’s rejection of the realist novel, an alternative literary format rooted in the ‘romance’ and the fantastic. 4

To put it simply, the gothic novel, with its use of the supernatural and fantastic, satisfied the surrealist opposition to rationalism. Walpole’s novel itself was a revolt against reason, in his words:

I have not written the book for the present age, which will endure nothing but cold common sense. 5

Tanning, with her love of authors like Ann Radcliffe, had given into the allure of the psycho-drama of gothic fiction from a young age:

Gothic fantasy was very influential in my life. It allowed the possibility of creating a new reality, one not dependent on bourgeois values but a way of showing what was actually happening under the tedium of daily life. Of curse, I was always thrilled by terror and chaos also. 6

The bourgeois values that Tanning was burdened with were different to those that the male surrealists opposed. Women were expected to remain in the domestic sphere, they had to be maternal and gentle, they had to marry a gentleman of good means. Gothic fantasy could serve as a critique of their societal role, it allowed women to explore sexual desires.

After all, what is a gothic novel without a haunted castle or home, and who could best haunt these spaces, than the women burdened by domesticity?

With her ability to float in between the real and the imagined, Tanning held the power to access unknown realms. Drifting through doors and passageways, the figures on her canvases are often spectral, nocturnal, in a state of flux and transformation, while the domestic spaces she portrays are ripe with night magic. 7

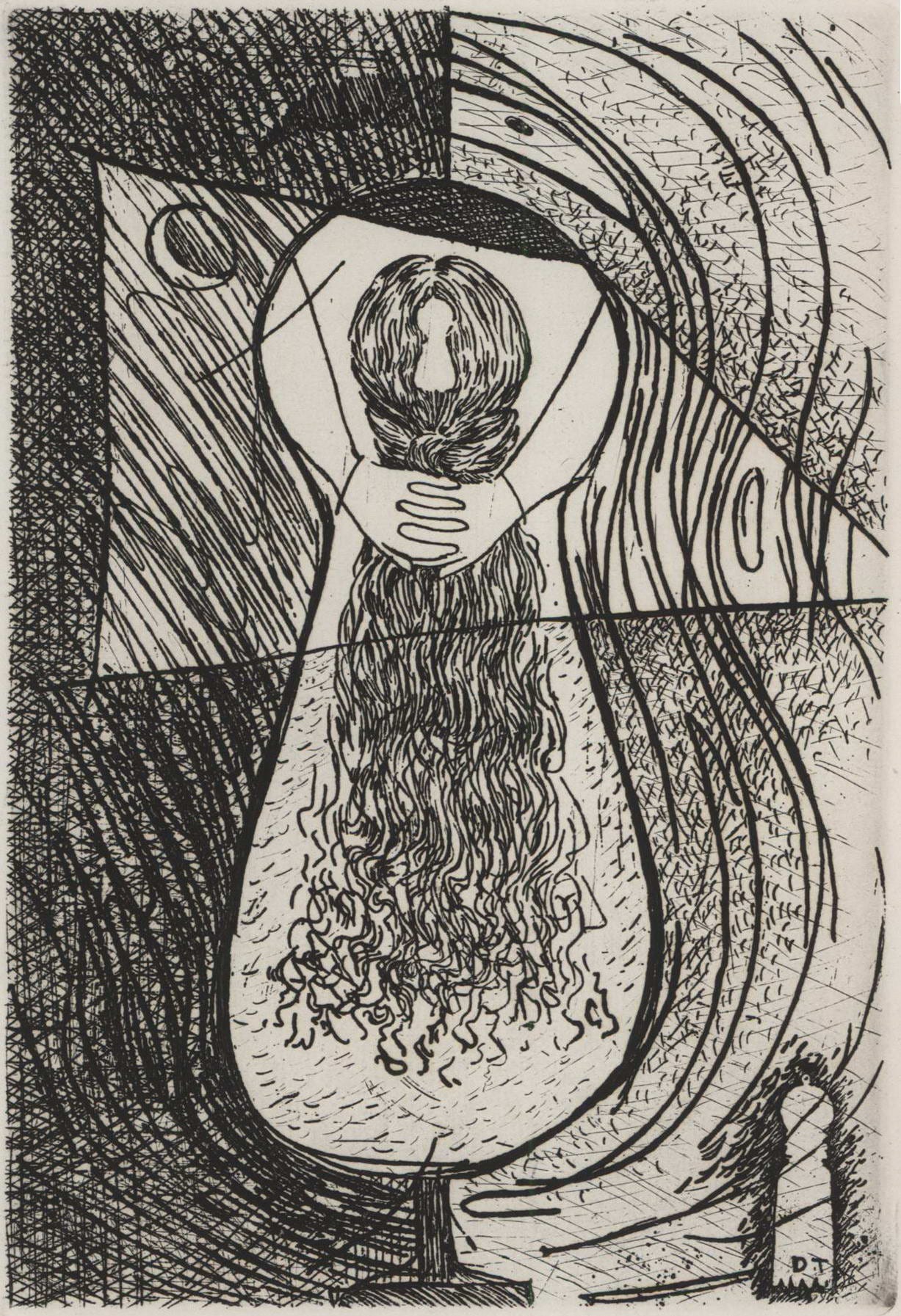

In 1947, one of her etchings was featured in the International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Galerie Maeght in Paris. Tanning’s piece fit perfectly in the show, which focused on magic, alchemy and myth. The etching depicts a woman’s body in the shape of a keyhole. I will leave you with Tanning’s explanation of the work:

…about leaving the door open to the imagination so that the viewer sees something else every time. 8

I hope you have enjoyed this little introduction to Dorothea Tanning and her work. She is a fascinating artists who lived until she was 101 - and she did not stop working for her whole life, she even published a poetry collection a year before her death. I urge you to continue reading about her, the different mediums she utilised, and the many ways in which she innovated whatever she laid her hands on.

If you are someone who is interested in learning more about painting and literature through the prism of magic and folklore, please consider subscribing to this newsletter and followings its visual companion.

Thank you for reading.

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bibliography

Ades, Dawn. ‘Dorothea Tanning’. The Burlington Magazine 161, no. 1394 (2019): 410–14.

Carruthers, Victoria. ‘Dorothea Tanning and Her Gothic Imagination’. Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 5, no. 1–2 (2011): 134–58.

Gruen, John. ‘Among the Sacred Monsters’. ARTnews 87, no. 3 (1988): 178–82.

Lumbard, Paula. ‘Dorothea Tanning: On the Threshold to a Darker Place’. Woman’s Art Journal 2, no. 1 (1981): 49–52.

Mahon, Alyce. ‘Of Kings and Queens: Alchemical Desire and the Imagination’. In Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity, edited by Gražina Subelytė and Daniel Zamani, 59–70. Munich: Prestel, 2022.

Matheson, Neil. Surrealism and the Gothic: Castles of the Interior. London ; New York: Routledge, 2018.

Sabor, P. Horace Walpole The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge, 1987.

Paula Lumbard, ‘Dorothea Tanning: On the Threshold to a Darker Place’, Woman’s Art Journal 2, no. 1 (1981), 50.

Dawn Ades, ‘Dorothea Tanning’, The Burlington Magazine 161, no. 1394 (2019), 410.

Victoria Carruthers, ‘Dorothea Tanning and Her Gothic Imagination’, Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 5, no. 1–2 (2011), 135.

Neil Matheson, Surrealism and the Gothic: Castles of the Interior (London ; New York: Routledge, 2018), 2.

P Sabor, Horace Walpole The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge, 1987), 90.

Carruthers, Dorothea Tanning and Her Gothic Imagination, 135.

Alyce Mahon, ‘Of Kings and Queens: Alchemical Desire and the Imagination’, in Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity, ed. Gražina Subelytė and Daniel Zamani (Munich: Prestel, 2022), 68.

John Gruen, ‘Among the Sacred Monsters’, ARTnews 87, no. 3 (1988), 182.

Yet another excellent article and a wonderful introduction to the work of a truly talented artist. Thank you for sharing!