Dear coven,

For this week’s enchantment - a weekly series in which I share a work of art motivated by magic - I chose Maya Deren’s Witch’s Cradle (1943). Enchantment of the week is a weekly series in which I talk about works of art motivated by magic. These usually follow an introduction of the artist from the previous week. You can read the introduction to Maya Deren here.

Witch’s Cradle, named after a torture device for suspected witches, is filled with drama, movement and incompleteness.

There is beauty in unfinished things, the incompleteness illuminates roads not taken. There is a sense of voyeurism to seeing an artist’s abandoned project. In this instance, the film gives us clues to ideas that Maya Deren continued in her oeuvre, as well as ones that she dropped.

One of the many legends surrounding Maya Deren’s persona is her casting as a witch. Her involvement with Haitian Vodou and her carefully crafted image paint the irresistible picture of her as an occult priestess. Deren seemed to possess a magnetic quality that drew people to her. Thirty years after her death, Gregory Bateson described her as ‘Lilith’:

"Why Lilith?" "Because," he replied, "that was her order; that was her goddess.” 1

So, is Witch’s Cradle supposed to be some form of ritual that makes us, the viewer, fall into a trance and draw us to Deren? Perhaps. But it’s hard to say what the film’s intention truly was, as it was never finished.

What we know about Deren is that she believed in the transformative power of cinema and that she saw film as its own beast that should not be conflated with other forms of art:

A radio is not a louder voice, an airplane is not a faster car, and the motion picture (an invention of the same period of history) should not be thought of as a faster painting or a more real play. All of these forms are qualitatively different from those which preceded them. They must not be understood as unrelated developments, bound merely by coincidence, but as diverse aspects of a new way of thought and a new way of life. 2

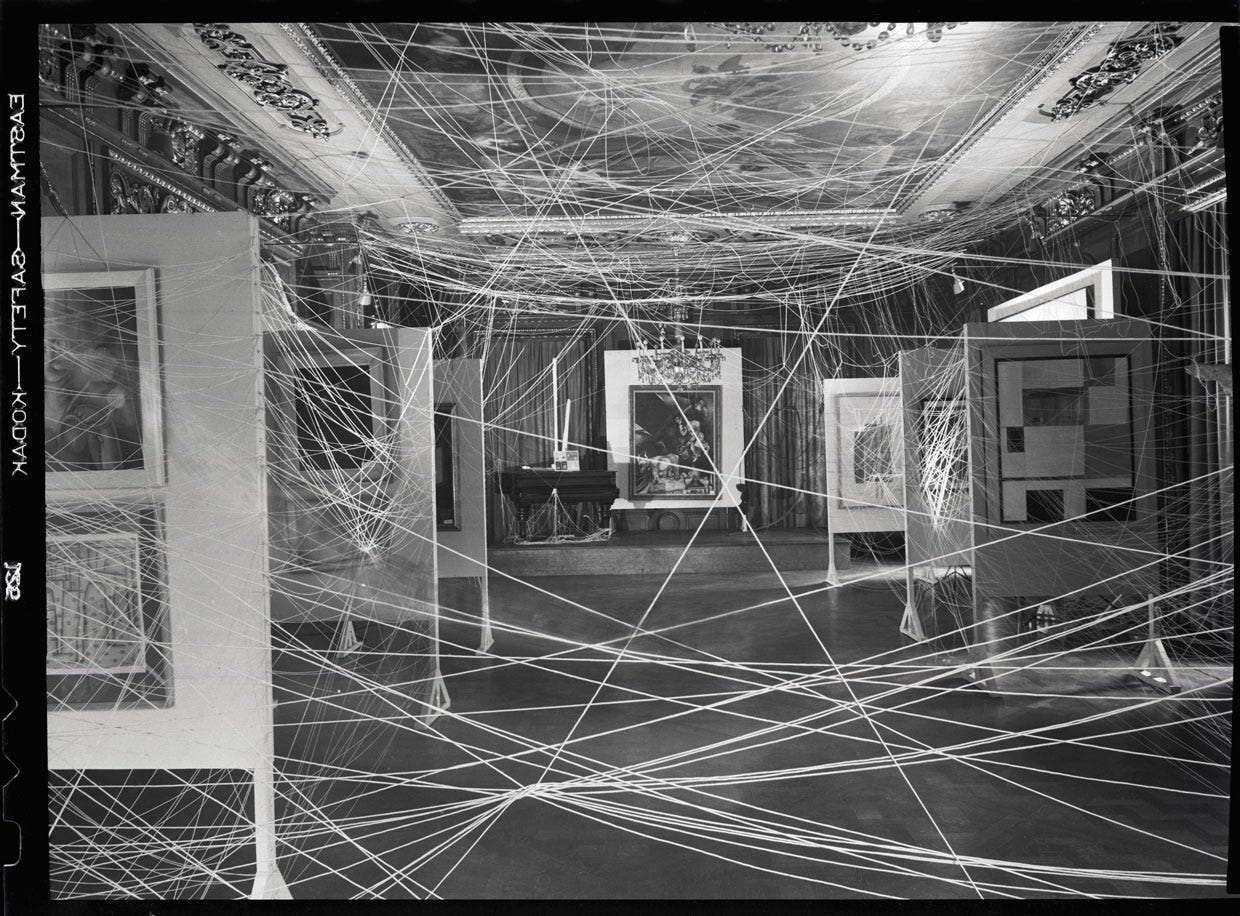

Witch’s Cradle was her first solo directorial project. She noted that she does not see it at all as complete or representative of her approach. The main issue seemed to stem from her limited access to the filming location - Peggy Guggenheim’s The Art of This Century gallery on 30 West 57th Street in Manhattan, New York City. She was allowed to film at the gallery for 10 days during a period of exhibition change-over.

The Art of This Century Gallery provided a backdrop of an impressive modern art collection. The works of Georges Vantongerloo, Alberto Giacometti, Antoine Pevsner, Piet Mondrian, Jean Arp, and Marcel Duchamp were all within Deren’s reach. Perhaps this complimented her view of film as an art form, but at the same time, somewhat negated her strive for the medium’s independence.

Marcel Duchamp, a giant in modern art, is prominently featured in this film and several scenes allude to his work. According to her shooting script, Deren planned for six sequences, each of which designated an object, action, fixation: "Brevoort and Terrace"; 'Alive String"; "String Travel"; "Plunge and Animation"; "Idol Sequence"; and "Balloon, Birds, Eye.” 3 Within the sequences, Duchamp’s work plays a part, namely his installation for the First Papers of Surrealism exhibit of 1942, also called the sixteen miles of string.

It has been posited that Deren re-purposed Duchamp’s work to allude to the idea of the labyrinth, with its ambiguous suggestion of passageway and imprisonment:

If the classical story follows a straight line that incorporates occasional detours, the labyrinth represents a different journey. 4

The string makes a journey in Deren’s film, it crawls through the narrative as it transforms from a noose into veins, all the while seemingly pulled by a dark, nearly invisible thread. The string is as obstructive as it is vital. It is the lifeblood of an idea and its death.

We cannot say for certain what Deren planned for this film, but the fact that it is unfinished along with our constant desire to know - what is this really about - speaks to the frustration that comes with not knowing, not understanding. This frustration stems for our own wish for closure, our comfort in the beginning, middle, and end. Without the latter, we are left to linger. Let us. Let us linger, let us be haunted.

Thank you for reading.

If you wish to learn more about artworks and artists motivated by magic, please consider subscribing to this newsletter.

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bibliography

Deren, Maya. ‘Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality’. Daedalus 89, no. 1 (1960): 150–67.

Gunning, Tom. "The End Is the Beginning: The Labyrinth in American Avant-Garde films" (lecture, The Louvre, Paris, France, 2007).

Keller, Sarah. ‘Frustrated Climaxes: On Maya Deren’s “Meshes of the Afternoon” and “Witch’s Cradle”’. Cinema Journal 52, no. 3 (2013): 75–98.

Neiman, Catrina. ‘An Introduction to the Notebook of Maya Deren, 1947’. October 14 (1980): 3–15.

Catrina Neiman, ‘An Introduction to the Notebook of Maya Deren, 1947’, October 14 (1980), 15.

Maya Deren, ‘Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality’, Daedalus 89, no. 1 (1960), 166.

Sarah Keller, ‘Frustrated Climaxes: On Maya Deren’s “Meshes of the Afternoon” and “Witch’s Cradle”’, Cinema Journal 52, no. 3 (2013), 89.

Tom Gunning, "The End Is the Beginning: The Labyrinth in American Avant-Garde films" (lecture, The Louvre, Paris, France, 2007).

this sounds brilliant, thank you for sharing