On the 25th of September 1922, the founder of Surrealism, André Breton, and his wife, Simone Kahn-Breton, hosted the poets René Crevel, Max Morise, and Robert Desnos in their Parisian home on 42 rue Fontaine. Holding hands around a table under dimmed lights, they witnessed Crevel enter a trance, uttering words and stringing together sentences that he could not recall when awakened. Immediately after, Robert Desnos experienced a similar state, one that Breton would identify as a ‘sleeping state’, he described the séance itself as a ‘sleeping session’. 1

What followed were months of these sleeping sessions. From Max Ernst, to Giorgio de Chirico, to Man Ray, a flock of proto-surrealists gathered to summon, at least in appearances, some form of spirit. Some were more adept than others. Crevel and Desnos would easily slip into a trance during which they would recount stories, answer questions and write what came from within (or beyond?) on paper. They made telepathic contact with acquaintances in New York; they dictated poems; their bodies contracted.

The sessions were filled with intensity:

We’re living simultaneously in the present, the past, and the future. After each séance we’re so dazed and broken that we swear never to start up again, and the next day all we can think about is putting ourselves back in that catastrophic atmosphere. 2

These experiments soon became violent. Crevel predicted that everyone present at the sessions would die of tuberculosis. Desnos became difficult to wake up, to the point of requiring doctor’s assistance. He attempted to stab a participant, who poured a jug of water on him, with a penknife. Attendants went missing and were then discovered in a side room, attempting to hang themselves upon Crevel’s instigation. 3 Things were getting out of hand, as described by Aragon:

Those who submit themselves to these incessant experiments endure a constant state of appalling agitation, become increasingly manic. They grow thin. Their trances last longer and longer. They don’t want anyone to bring them round anymore. They go into trances to meet one another and converse like people in a faraway world where everyone is blind, they quarrel and sometimes knives have to be snatched from their hands. The very evident physical ravages suffered by the subjects of this extraordinary experiment, as well as frequent difficulties in wrenching them from a cataleptic death-like state, will soon force them to give in to the entreaties of the onlookers leaning on the parapet of wakefulness, and suspend the activities which neither laughter nor misgivings have hitherto interrupted. 4

In the spring of 1923, Breton put an end to the sessions.

So, what happened? Were the surrealists possessed by some unknown and dangerous spirit? In a way, absolutely.

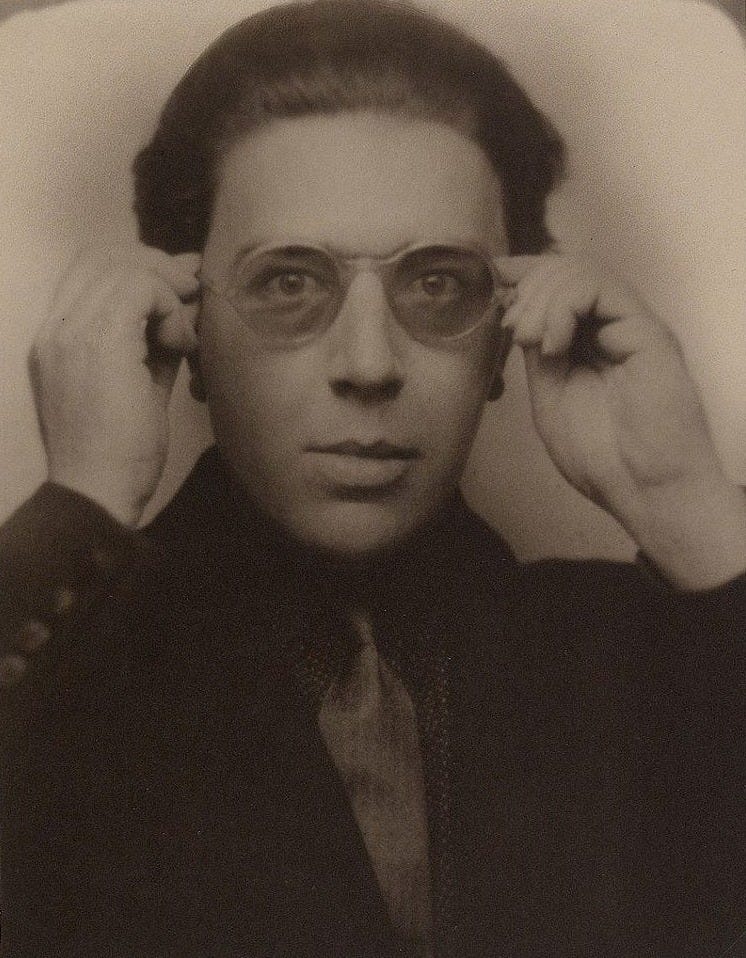

Surrealism was officially founded by André Breton in 1924. Originally, it was a literary exercise, not only was Breton a poet, but in his surrealist manifesto, he stated that the chief activity of Surrealism was in the field of verbal reconstruction. The objective of Surrealism was the infinite expansion of reality as a substitute for the previously accepted dichotomy between real and the imaginary. The official definition given by Breton was as follows:

SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its purse state by which one proposes to express, verbally, by any means of the written word, or in any other manner, the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by the thought in the absence of any control exercised by reason exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern. 5

Automatism was one of the tools used by the surrealists to suppress the control of the conscious. It generally involved writing and drawing without conscious thought, for example, by writing as fast as possible without stopping.

So, in the 1920s, automatism became central to Surrealism in its foundational moment, and spiritualist mediums proved instrumental in this regard - the actions of clairvoyants, and those capable of communicating with the dead were interpreted as automatic and were therefore stimulating to the surrealists.

Dear coven, today, I wish to explore this curiosity about prophecies and communications with the beyond.

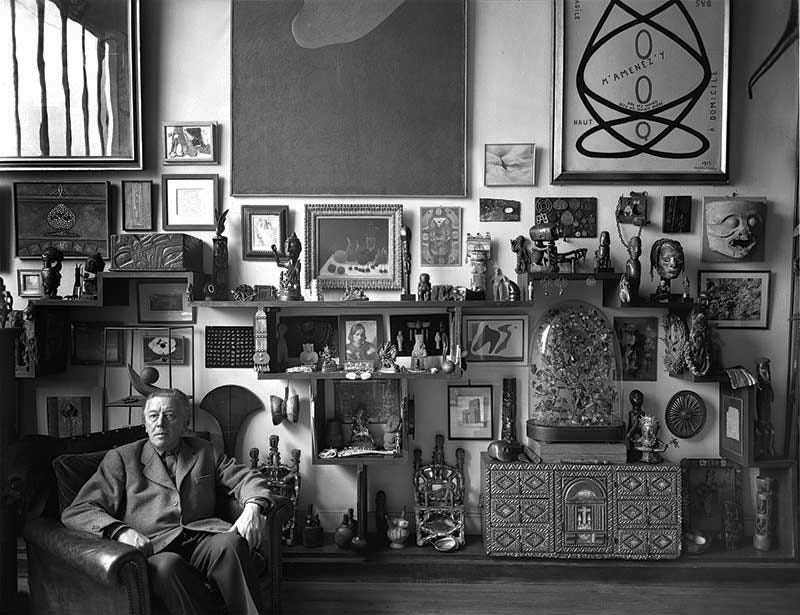

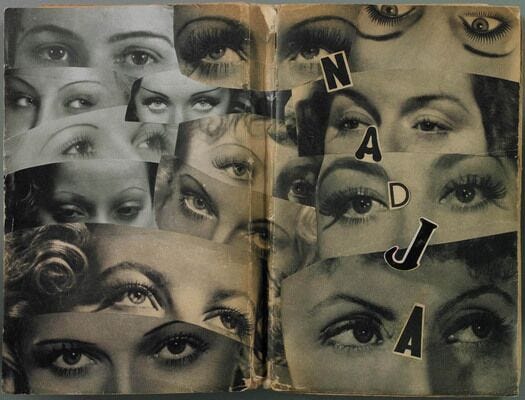

It was no secret that Breton was captivated by mediums, as evidenced by his visits to local fortune-teller, Madame Sacco, recounted in his novel Nadja. 6 At the time, this attraction to mediums was deplored by critics:

I concede that the breakneck career of Surrealism over rooftops, lightning conductors, gutters, verandas, weathercocks, stucco work—all ornaments are grist to the cat burglar’s mill—may have taken it also into the humid backroom of spiritualism. But I am not pleased to hear it cautiously tapping on the windowpanes to inquire about its future. Who would not wish to see these adoptive children of revolution most rigorously severed from all the goings-on in the conventicles of down-at-heel dowagers, retired majors, and émigré profiteers? 7

It seems that Breton himself wished to distance Surrealism from the actions of mediums, despite his fascination. Describing his experiments between 1922 to 1923 as ‘sleeping sessions’ as opposed to séances is evidence of this reluctance. The sleeping sessions overall were referred to as the time of slumbers.

This could be because he sought a different ideological position, one closer to psychoanalysis, so pointing to the dream-state would be most logical. It’s a viable assumption that Breton did not consider the association to mediums as beneficial as the idea of a dream-like state - this way, his movement could more easily coincide with Freud’s theories on dreams, the ultimate utilising of the unconscious, and popular studies on somnambulism. It has to be kept in mind that the word séance can also simply mean ‘session’ in French, and psychoanalytical sessions are also called séances. Still, given that Breton credited spiritualists as instrumental influences on these experiments, and the set-up of their gatherings, we can assume that to a certain extent, least of all in appearances, the word séance can be understood as meaning spiritual séance.

If Breton’s actions convey a defiance in directly associating Surrealism with Spiritualism, the desire to be allied with Freud instead is not the solitary cause. Breton would have witnessed the rise of mediums and their sceptics.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Spiritualism was in the air. Its popularity brought forth a rise in scepticism and fraudulence. Even spiritualist periodicals of the time took up the practice of exposing fakery in an attempt to show their own validity. Amongst the recorded incidents were faked spirits in photographs, reports of how infamous mediums like Florence Cook and Rosina Showers were caught cheating, and the fraud of spiritualists Henry Slade and Dr Monck. 8 In 1876, Spiritual Magazine wrote:

It would puzzle an outsider to guess why publications professedly devoted to Spiritualism, and men occupying conspicuous positions in the movement, should be found using their every means to crush the greatest medium that has appeared in modern times. We have not, however, to seek far for the cause: trickery and cheating have become so prevalent in connection with spiritual phenomena, that the grandest movement of this age appears to be in danger of being overwhelmed by one vast flood of deception and imposture. Hardly a week passes but some so-called medium is detected in the act of deceiving; and thus, not only trifling with one of the most sacred of subjects, but practising a fraud a thousand times more heinous, morally, than any commercial swindle. 9

The feeling was that any form of trickery threatens the legitimacy of the entire movement, so it was only natural for spiritualist publications to strongly condemn fraudsters.

Still, Spiritualism reached a peak in popularity, by the early 1920s it had spread like wildfire. In Britain, it was reported that Spiritualism was rampant amongst women and getting a hold upon men in an ‘alarming fashion’, you could encounter it in both Mayfair and in the remotest village. 10

France also saw a rise in Spiritualism with mediums such as Eva Carrière, who was investigated by Arthur Conan Doyle, and whose photographs featured ectoplasms and a nude Carrière channelling spirits. 11 There was also Valentine Dencausse, known as Madame Fraya, who was famous for her palm readings in Paris in the early 1900s with clients ranging from princesses to emperors. 12

But why did this happen? Why then?

Well, millions of lives were lost in the First World War, and by its end the world was still in the grips of a pandemic. These events left countless people grieving, and where there is grief and trauma, there is opportunity.

You might also be thinking – what about the Christians, did they abandon God for spirits?

Spiritualism and its relationship to Christianity was complex with some viewing it as anti-clerical, while others deliberated if the belief in spiritualists could enhance the belief in God. Spiritualism was seen as a more scientific supernatural, since it is supported by scientific theory or empirical evidence while also at least partially eluding scientific tests, instruments, or measurements. 13 One of these tests, of course, was the séance, it was how spiritualists presented their evidence and observation.

Spiritualism naturally provoked Catholicism, much guidance on the teachings of the Church about Spiritualism was published. It was supposed that there could be outside intelligences that communicate to mediums and those engaging in séances and that those voices did not necessarily have to be Satanic, and yet:

What we know for certain is that the attempt to communicate with the unseen through spiritualistic practices is extremely dangerous and that the Church in all ages has very wisely denounced it. 14

However, Spiritualism provided something that the Church could not.

What characterised grief during the nineteenth century was individualism and materiality. 15 During the war, families could not perform these practices – not only was death nationalised through the idea of the fallen hero, regardless of status or background, but more often than not there was no individual to bury. Thus, the séance became a surrogate ritual – it was direct and personal and could substitute a missing body. Those who favoured Spiritualism over Christianity most likely did so simply due to the preference of speaking directly to a person that has passed, as opposed to praying to an omnipotent figure for their salvation. Mediums also had the ability to fill gaps – how did the soldier die, what was his fate, what were the last words, was it painless?

This is the context of the attitude towards Spiritualism before and at the time of Surrealism’s sleeping sessions. So, let us consider the surrealist interest in mediumship with this in mind.

Firstly, the Church’s rejection of Spiritualism would have appealed to Breton. The surrealists’ orientation was predominantly left-wing, with a profound antipathy towards institutionalised religion, as exemplified in the 1920s by Benjamin Péret’s notorious street performances of insulting Catholic priests to their faces.

![tumblr_lnih4xJoZ11qj1po4o1_500[1] tumblr_lnih4xJoZ11qj1po4o1_500[1]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Ef8p!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F65f00f47-e721-477e-a8bc-73eded2f928f_391x615.jpeg)

Secondly, Surrealism owed many of its ideas on automatic writing to mediumship. The idea of a person becoming both transmitter and recorder by remaining partially conscious mimics the practice of clairvoyants communicating with the dead. This has been explored by psychologists such as Theodore Flournoy in his publication, which was praised by the surrealists - From India to the Planet Mars: A Study of a Case of Somnambulism with Glossolalia (1900) - the first analysis of Spiritualism and psychology in tandem.

Breton credited psychiatric research for automatism, specifically the work of psychologist Pierre Janet. Janet’s approach was heavily influenced by his discovery that most successful mediums wrote without any conscious awareness or need for the presence of another person to record their words. A crucial distinction between mediums and the mentally ill seemed to be the source of their automatic activity – in psychiatry it was the unconscious, in mediumship, the dead. Men like Janet, Freud and Jean-Martin Charcot saw hysteria as a force that unleashed what the conscious mind suppressed. There is much to be said about how women were treated by these men, but that is a deep dive for another time.

I would argue that women, however, are a crucial reason why Breton was interested in Spiritualism.

The fact that some of the most famed mediums were female is significant to Surrealism, a movement which already viewed women as mediating links between the irrationality of the subconscious and reality. There is also something to be said about Surrealism’s potential sexual attraction to Spiritualism, and if that was the case, they would not have been the only ones.

In the Victorian era, mediums and their powers broke the rules of social decorum – the darkened parlour, the holding of hands regardless of gender, the intimate quiet and the sudden gasps:

Faces and knees were caressed while the lights were out, gentlewomen submitted to be kissed by strangers, and the most private recesses of the past and present were exposed to the public eye. 16

Spiritualism allowed for an entirely new relationship between men and women, one outside the confines of sex and marriage, as it shattered the social dichotomies of the genders. Many women were empowered by their spiritualistic potential. Mediums, who were already in a marriage, experienced a significant shift of the power-dynamics between them and their husbands – a husband could not demand of his wife to stop her calling of communicating with spirits, nor could he condemn a relationship between his wife and her researcher or patron. Additionally, by choosing a pseudonym for their mediumship practice, these women were liberated from the names of their fathers and husbands. Women who were not married could also benefit from Spiritualism, they were no longer spinsters, but notorious mystics with extravagant lifestyles.

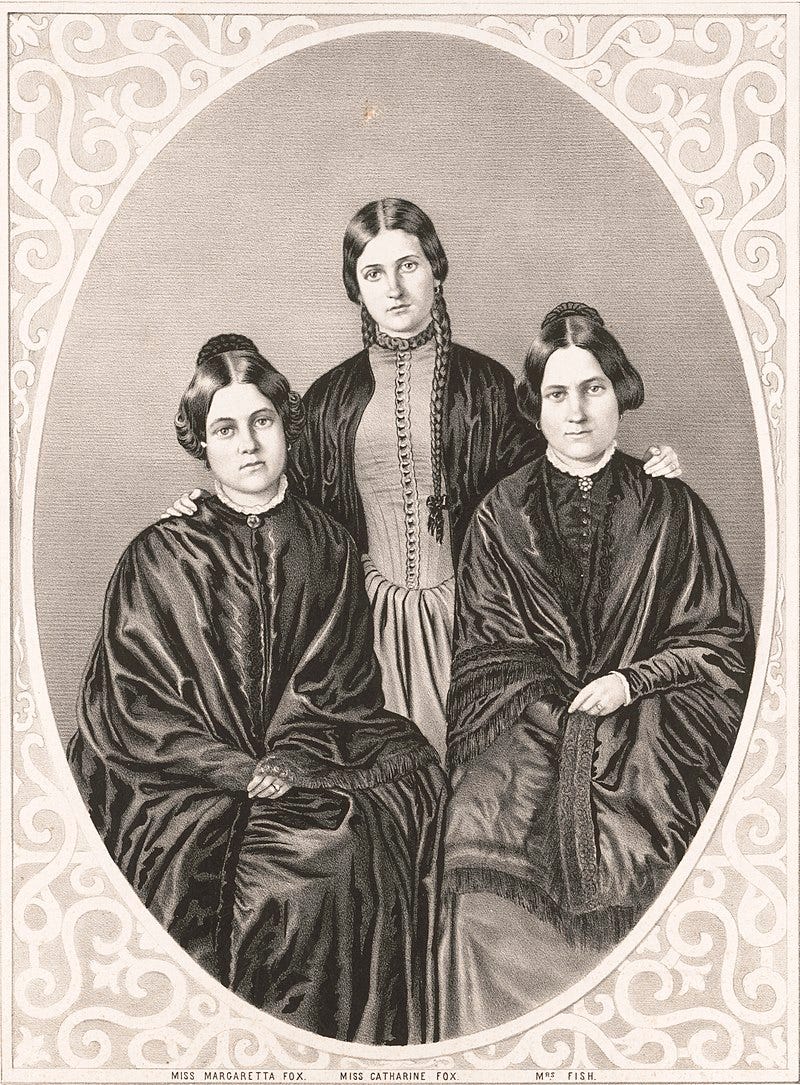

The Fox sisters are amongst the most well-known mediums. They did not have men in their lives who they could rely on – they were abandoned by their alcoholic father, and Leah Fox was only fourteen when she married a much older man, who then deserted her. She was looking for a way out and the mysterious rapping sounds in their Rochester house, allegedly a form of communication for spirits, gathered the attention of the local press. For the Fox sisters the occult was empowering, they were working class materialisation mediums who moved from humble beginning to relatively comfortable middle-class lifestyles. 17

Similarly, it was documented that Eva Carrière, who developed her psychic abilities after her husband’s death, recognised the independence mediumship provided:

Eva C. is not a professional medium, i.e., she is not obliged to engage herself for sittings for money but can return at any moment to her parents and sisters. But she prefers her independence and lends her remarkable power freely to Mme. Bisson and her collaborators for scientific purposes, from gratitude for the years of hospitality enjoyed in the house of the Bisson family. She has no binding obligation towards them; she is fully in possession of her liberty and can discontinue the experiments whenever she likes. On the other hand, Mme. Bisson is undoubtedly under a moral obligation to the family of Eva C. to guard her against any injury to her health, or danger to her mind, and she also has to undertake a legal responsibility for the girl against such things as negligence resulting in bodily injury. 18

Mediumship gave women autonomy, but even more importantly, power. Women could break out of the role of nurturer and vessels of life as they had the potential to tap into the greatest unknown and life’s antithesis – death.

Spiritualism could be scandalous in ways that did not involve the dead, and in this sense one can grasp Surrealism’s own flirtation with séances. The spirits that these mediums got in contact with were not always fallen heroes, they could be flirtatious lovers or provocateurs. It was the same flirtation Breton encouraged women to engage with when it came to their ‘irrationality’. As a predominantly male movement, however, Surrealism saw these women’s powers as supplementary for their own creative cycle, so by seeing them as vessels for death/irrationality, it was obviously not particularly empowering.

Breton’s fascination with mediums was piqued by their history of renouncing authority and societal norms. This is precisely the kind of calling he hoped women would follow and their ability to fall into a state that disassociates the body from the mind and lifts the veil of reality was a cherished skill, as he put it:

I ask, once again, that we submit ourselves to the mediums who do exist, albeit no doubt in very small numbers, and that we subordinate our interest-which ought 110t to be overestimated-in what we are doing to the interest which the first of their messages offers. Praise be to hysteria, Aragon and I have said, and to its train of young, naked women sliding along the roofs. The problem of woman is the most wonderful and disturbing problem there is in the world. 19

(Breton ‘stop being weird about women at least for once challenge)

The entire origin of the sleeping sessions seems to have been instigated by a female medium:

Two weeks ago … René Crevel described to us the beginnings of a ‘spiritualist’ initiation he had had, thanks to a certain madame D. This person, having discerned particular mediumistic qualities in him, had taught him how to develop these qualities; so it was that, in the conditions necessary for the production of such phenomena (darkness and silence in the room, a ‘chain’ of hands around the table), he had soon fallen asleep and uttered words that were organized into a generally coherent discourse, to which the usual waking techniques put a stop at a given moment. 20

This in itself is revelatory to the power women had to capture the male imagination. To Breton, mediums expressed a rich inner world, and an irrationality that was seen as distinctly feminine.

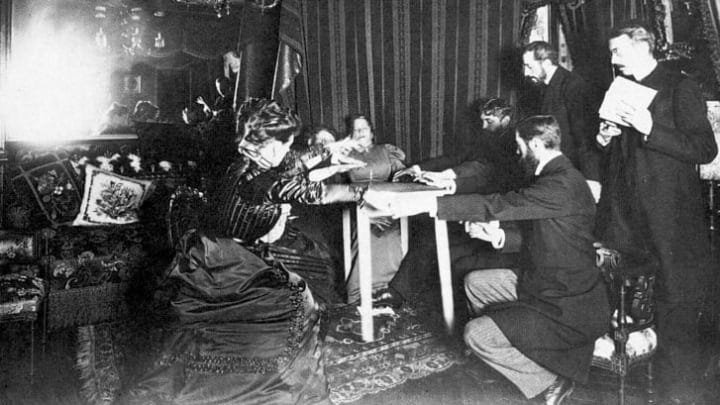

Rachel Leah Thompson calls attention to automatic writing being written upon and through women’s bodies. For example, in Man Ray’s Waking Dream Séance (1924) (pictured below) we see Simone Kahn-Breton taking dictation from ‘beyond’ as the male surrealists surround her and observe her intently. She is both the centre of the autographic process and utterly unacknowledged. 21

Despite all of this, Breton was resistant to associate Surrealism with Spiritualism any further than in its theatricality:

It goes without saying that at no time, starting with the day we agreed to try these experiments, have we ever adopted the spiritualistic viewpoint. As far as I’m concerned, I absolutely refuse to admit that any communication whatsoever can exist between the living and the dead. 22

Even though Spiritualism was alluring, Breton was understandably resistant to being associated with fraudulence, it would risk the movement not being taken seriously and paint the surrealists as charlatans. He wanted Surrealism to be seen as provocative and avant-garde, but he could not risk it losing its intellectual edge.

Ultimately, they were not so interested in the beyond, but in what was within.

So, what are we to make of the ‘sleeping sessions’? Breton’s reluctance to talk to the dead does not negate the correspondence between the sessions and Spiritualism, but it does illustrate his desire to illuminate the link to the psyche, rather than the psychical. What unites both fields is the exploration of the unconscious.

With this in mind, we can understand the darkened rooms and the loss of consciousness, which was ultimately, not a loss, but a conquest.

So yes, yes they were possessed.

I hope you have enjoyed this exploration of Surrealism’s relationship to Spiritualism. If you wish to learn more about art and literature through the prism of magic, please consider subscribing to this newsletter and following its visual companion.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bibliography

Aragon, Louis. A Wave of Dreams. Translated by Susan De Muth. London: Thin Man Press, 2010.

Bauduin, Tessel. ‘The Occultation of Surrealism: A Study of the Relationship between Bretonian Surrealism and Western Esotericism’. Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2012.

Bauduin, Tessel. Surrealism and the Occult: Occultism and Esotericism in the Work and Movement of André Breton. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014.

Benjamin, Walter. ‘Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia’. In Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, edited by Peter Demetz, 177–92. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Breton, André. The Lost Steps. Edited by Mark Polizzotti. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

Cannon, A. “Socioeconomic Change and Material Culture Diversity: Nineteenth Century Grave Monuments in Rural Cambridgeshire”. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1986.

Cecil, Edwawrd. ‘The Popularity of Spiritualism’. The Globe, 1919.

Curl, James Stevens. The Victorian Celebration of Death. Trowbridge and London: Redwood Press, 1972.

Falcon, Kyle. ‘The Ghost Story of the Great War: Spiritualism, Psychical Research and the British War Experience, 1914-1939.’, 2018.

Galvan, Jill. The Sympathetic Medium: Feminine Channeling, the Occult, and Communication Technologies, 1859–1919. Cornell University Press, 2010.

Home, D.D. ‘To the Editor of the “Spiritual Magazine”’. The Spiritual Magazine, 1876.

Lamont, Peter. ‘Spiritualism and a Mid-Victorian Crisis of Evidence’. The Historical Journal 47, no. 4 (2004): 897–920.

Mello, Antônio da Silva. Mysteries and Realities of This World and the Next. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1960.

Polizzotti, Mark. ‘Profound Occultation’. Parnassus 30, no. 1–2 (2008): 1–37.

Schrenck-Notzing, Baron von. Phenomena of Materialisation: A Contribution to the Investigation of Mediumistic Teleplastics. Translated by E.E. Fournier d’Albe. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1923.

Tarlow, Sarah. Bereavement and Commemoration: An Archaeology of Mortality. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1999.

Thompson, Rachel Leah. ‘The Automatic Hand: Spiritualism, Psychoanalysis, Surrealism’. Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture, no. 7 (2004): 2–14.

Thurston, Herbert. ‘Catholics and Spiritualism’. An Irish Quarterly Review 15, no. 57 (1926): 79–94.

Tromp, Marlene. ‘Spirited Sexuality: Sex, Marriage, and Victorian Spiritualism’. Victorian Literature and Culture 31, no. 1 (2003): 67–81.

Tromp, Marlene. Altered States: Sex, Nation, Drugs, and Self-Transformation in Victorian Spiritualism. New York: SUNY Press, 2006.

White, Christopher G. Other Worlds: Spirituality and the Search for Invisible Dimensions. Harvard University Press, 2018.

Tessel Bauduin, ‘The Occultation of Surrealism: A Study of the Relationship between Bretonian Surrealism and Western Esotericism’ (Amsterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2012), 35.

Cited in Mark Polizzotti, ‘Profound Occultation’, Parnassus 30, no. 1–2 (2008), 5.

Bauduin, The Occultation, 61.

Louis Aragon, A Wave of Dreams, trans. Susan De Muth (London: Thin Man Press, 2010), 6-7.

André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972),26.

Tessel Bauduin, Surrealism and the Occult: Occultism and Esotericism in the Work and Movement of André Breton (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014), 66.

Walter Benjamin, ‘Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia’, in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, ed. Peter Demetz (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978), 180.

Peter Lamont, ‘Spiritualism and a Mid-Victorian Crisis of Evidence’, The Historical Journal 47, no. 4 (2004), 915.

D.D. Home, ‘To the Editor of the “Spiritual Magazine”’, The Spiritual Magazine, 1876, 384.

Edward Cecil, ‘The Popularity of Spiritualism’, The Globe, 1919; Rose Staveley-Wadham, ‘Understanding the 1920s Spiritualism Revival’, The British Newspaper Archive (blog), 14 October 2021.

Baron von Schrenck Notzing, Phenomena of Materialisation: A Contribution to the Investigation of Mediumistic Teleplastics, trans. E.E. Fournier d’Albe (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1923).

Antônio da Silva Mello, Mysteries and Realities of This World and the Next (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1960).

Christopher G. White, Other Worlds: Spirituality and the Search for Invisible Dimensions (Harvard University Press, 2018), 4.

Herbert Thurston, ‘Catholics and Spiritualism’, An Irish Quarterly Review 15, no. 57 (1926), 94.

See Falcon, The Ghost Story of the Great War, 220; Sarah Tarlow, Bereavement and Commemoration: An Archaeology of Mortality (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1999), 122-123, 132-33, A. Cannon, “Socioeconomic Change and Material Culture Diversity: Nineteenth Century Grave Monuments in Rural Cambridgeshire” (PhD diss., Cambridge University, 1986), and James Stevens Curl, The Victorian Celebration of Death (Trowbridge and London: Redwood Press, 1972)

Marlene Tromp, ‘Spirited Sexuality: Sex, Marriage, and Victorian Spiritualism’, Victorian Literature and Culture 31, no. 1 (2003), 67

See Jill Galvan, The Sympathetic Medium: Feminine Channeling, the Occult, and Communication Technologies, 1859–1919 (Cornell University Press, 2010) and Marlene Tromp, Altered States: Sex, Nation, Drugs, and Self-Transformation in Victorian Spiritualism (SUNY Press, 2006).

Schrenck-Notzing, Phenomena of Materialisation, 27.

Breton, Manifestoes, 180.

Breton, The Lost Steps, 92.

Rachel Leah Thompson, ‘The Automatic Hand: Spiritualism, Psychoanalysis, Surrealism’, Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture, no. 7 (2004), 14.

Breton, The Lost Steps, 92.

Loved this! I'm obsessed with the relationship between artists and spiritualism

This is so great! I read a lot about spiritualism and seances when I was writing a novella (which will someday appear here on Substack), but I learned tons more from your post, and I loved learning the connections between Surrealism and Spiritualism. (Also, we are supposed to have a "personal mission statement" at work--and I never do it. Now I kinda want "praise be to hysteria" to be my new mission statement.)