The protagonist, instead of undertaking the long voyage of search for adventure, finds instead that the universe itself has usurped the dynamic action which was once the prerogative of human will, and confronts her with a volatile and relentless metamorphosis in which her personal identity is the sole constancy.

- Maya Deren

What is identity? Where does it reside? Does it materialise with our first cry and dissipate with our last breath - both acts marked by our names on dotted lines? Does it follow us as we move through cities and countries? Does it manifest in our words, spoken and written, or does it dance between fingers taps, crossed legs and widened eyes? Does it marry itself to our vocations?

Eleonora Derenkowski was born in Kiev in 1917. If identity is in a name and a place, both Eleonora and Kiev were left behind. The Derenkowski family emigrated from Kiev to the United States in 1922, escaping from anti-Semitic pogroms and the chaos of the USSR. 1 Twenty years after bidding Kiev farewell, Eleonora Derenkowski became Maya Deren - Maya, after the Hindu goddess of illusion and creative force. The name was given to her by her future husband, Alexander Hackenschmied - who shed his name to simply Alexander Hammid.

Meeting Hammid brought more than just a new name, it brought new vision. Deren held a Master’s Degree in English Literature, her thesis titled Influences of the French Symbolist Movement Upon Anglo-American Poetry. At this point in time, while still Eleonora, she wanted to be a poet. Hammid, an accomplished photographer and cinematographer, introduced her to his camera and this brought forth a different desire for expression, one that aligned with her vision more than poetry, in her own words:

The reason that I had not been a very good poet was because actually my mind worked in images which I had been trying to translate or describe in words; therefore, when I undertook cinema, I was relieved of the false step of translating image into words, and could work directly so that it was not like discovering a new medium so much as finally coming home into a world whose vocabulary, syntax, grammar, was my mother tongue. 2

So, Eleonora became Maya and the poet became a filmmaker. Though traces of poetry remained. Deren’s close study of T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound manifests, perhaps unconsciously, in her first film with Hammid, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943).

This dreamlike, circular narrative assembles collections of objects, which echoes T.S. Eliot’s objective correlative, which Deren described in her thesis as ‘an ensemble of objects, a situation, a series of events as symbols of inner reality’. 3

This film, with its sensual artificial flower, its sleeping figure, and key toppling down the stairs, was unsurprisingly read as Freudian. Deren opposed this, in fact she spent the following years trying to shake this interpretation off her back, as evidenced in her program notes from 1949:

What complicated reasons the Freudians gave for that poor old poppy. What elaborate and involved analysis they did of me, explaining the deep and hidden motives that drove me to select, from among all flowers, an artificial poppy. 4

What I find interesting here is not the Freudian interpretation, but rather the objection and the program notes themselves.

Today, the filmmaker’s relation to their film is an object of extreme interest - think auteur theory, just as the actor is often connected to their films in some personal way - think method acting. In the 1940s the phenomenon of constructing mainstream film stars was norm and auterism was always a dominant model of stardom in alternative cinema. 5 Deren participated in this process both as filmmaker and as performer.

Deren gained marketing experience through her work as a personal assistant to dancer/choreographer Katherine Dunham. She then implemented strategic promotional campaigns for her own films - she used photographs of herself for visual materials, she appeared at the film screenings, she gave talks and wrote program notes.

Does this mean that Deren was constructing her persona akin to the movie stars of the 1940s? In a way yes, but her efforts were directed at exploiting the public’s desire for a certain image of bohemian womanhood. And it worked. We can see her effort’s success in the press’ reaction to Deren. 6

The New York World-Telegram, 1946:

A good deal of what Maya Deren says about her creative work in motion pictures sounds like long-hair double talk. But it is as agreeable to listen to as she is to look at.

Esquire, 1946:

Maya Deren experiments with motion pictures of the subcon- scious, but here is finite evidence that the lady herself is infinitely photogenic.

New Republic review, 1946:

A lot of people casually mention motion picture-making as an art. Down in Morton St., in Greenwich Village, lives a small- sized young woman with large gray eyes and an aggressive cloud of curly brown hair, whose belief in films as an art form amounts to a passion

The magic Deren possessed over her viewers manifested further in her personal life and in her friendships. Her Greenwhich village apartment with Hammid was frequented by visitors such as Dylan Thomas, John Cage, Salvador and Gala Dalí, and Anaïs Nin. Nin wrote about Deren in diary:

We gave [Deren] our time, our energy and even our money. . . . We believed in her as a filmmaker, we had faith in her, but we began to feel she was not human. ... We were influenced, dominated by her, and did not know how to free ourselves. 7

In fact, she had a lot to say about Deren and her words further nurture Deren’s magnetic persona, whether that persona was structured or not:

Last night we were excavating the Maya Deren mystery. We all sit in a circle and wonder why we do exactly what she commands us to do. We are subject to her will, her strong personality, yet at the same time we do not trust or love her wholly. We recognize her talent. We talk of rebellion, of being forced, of tyranny, but we bow to her projects, make sacrifices. 8

Nin starred in Deren’s film Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946), though the film led to a drift in their friendship. Nin did not speak favourably on the film:

The theme of interchangeable personalities is not clear, and I might even say that in destroying the characters, Maya destroyed the film. When gestures are broken at the party, heads cut off, it is not human beings who lose arms and heads but the film which loses its meaning. I feel this film is a failure. 9

Here, Nin expresses her opposition to Deren’s philosophy on individualism, one that she saw as antagonistic to her own beliefs. Additionally, once she saw the film, Nin was not pleased with how she was portrayed - while Deren was shot in soft focus, the harsh light on Nin’s face made her look more severe. She saw this as a betrayal.

This falling out, whether based on aesthetic or philosophical principles, has identity at its centre. Nin was unhappy with Deren’s forsaking of the individual, both visually and contextually. Indeed, while Deren might have crafted a persona, her films question individualism.

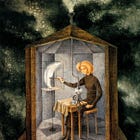

Deren was interested in the idea of possession, trance, and dance. The movement and repetition performed by her camera and her actors enhance the idea of filmmaking as a ritual:

I have called this new film ritual, not only because of the importance of the quality of movement, but because a ritual is characterized by the depersonalisation of the individual. The intent of such a depersonalisation is not the destruction of the individual; on the contrary, it enlarges him beyond the personal dimension, and frees him from the specializations and confines of "personality”. 10

Deren was immersed in performance, dance, and anthropology. She was the first to receive a Guggenheim fellowship for a film project, which she planned to use to travel to Haiti and create a film on dance and ritual. She abandoned this idea, perhaps due to questioning her own role as coloniser and the risk of trivialising rituals.

What led her to this incomplete project was what motivated her work in the first place - the depersonalisation of her characters, who do not follow the Western idea of individualistic and self-contained beings, but are instead fluid and dismembered. 11 By critiquing the Western individual, while participating in the commodification of persona, Deren reflects on her own status as an artist and a woman in postwar America.

So, who is Maya Deren? Is she Eleonora, who became Maya? Is she the woman with the Botticelli curls, pictured in her promotional materials? Is she the shadow she casts over an artifical poppy in Meshes of the Afternoon? Or the weaver in Ritual in Transfigured Time? Is she the bohemian artist of Greenwhich village or the maternal figure labelled ‘mother of avant-garde cinema’?

She is all. She is none.

I stand like a mirror before you. Have you your perfection to reflect in it? This is the aim of your life, to be a living mirror before every face that comes near you. Now . . . forswear all and go begging and be a mirror before the world. 12

-Maya Deren

I hope you have enjoyed reading this introduction to Maya Deren as much as I enjoyed writing it. All of her films are available to watch online for free, I highly recommend you do.

If you want to learn more about artists and artworks motivated by magic, please consider subscribing to this newsletter and followings its visual companion.

Thank you for reading.

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bibliography

Deren, Eleonora. ‘Influence of the French Symbolist Movement Upon Anglo- American Poetry’. Smith College, 1939.

Deren, Maya. ‘Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality’. Daedalus 89, no. 1 (1960): 150–67.

Deren, Maya. ‘Film in Progress: Thematic Statement’. Film Culture, no. 39 (1965).

Deren, Maya. ‘From the Notebook of Maya Deren, 1947’. October 14 (1980): 21–46.

Durant, Mark Alice. ‘Maya Deren: A Life Choreographed for Camera’. Aperture, no. 195 (2009): 42–47.

Keller, Sarah. ‘Frustrated Climaxes: On Maya Deren’s “Meshes of the Afternoon” and “Witch’s Cradle”’. Cinema Journal 52, no. 3 (2013): 75–98.

Millsapps, Jan L. ‘Maya Deren, Imagist’. Literature/Film Quarterly 14, no. 1 (1986): 22–31.

Mollona, Massimiliano. ‘Seeing the Invisible: Maya Deren’s Experiments in Cinematic Trance’ 149 (2014): 159–80.

Neiman, Catrina. ‘An Introduction to the Notebook of Maya Deren, 1947’. October 14 (1980): 3–15.

Nin, Anaïs. The Diary of Anaïs Nin 1944-1947 (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co, 1971).

Pramaggiore, Maria. ‘Performance and Persona in the U.S. Avant-Garde: The Case of Maya Deren’. Cinema Journal 36, no. 2 (1997): 17–40.

Mark Alice Durant, ‘Maya Deren: A Life Choreographed for Camera’, Aperture, no. 195 (2009): 42–47.

Jan L. Millsapps, ‘Maya Deren, Imagist’, Literature/Film Quarterly 14, no. 1 (1986), 23.

Eleanora Deren, "Influence of the French Symbolist Movement Upon Anglo- American Poetry," Thesis, Smith College, 1939, p. 137.

Millsapps, Maya Deren, Imagist, 26.

Maria Pramaggiore, ‘Performance and Persona in the U.S. Avant-Garde: The Case of Maya Deren’, Cinema Journal 36, no. 2 (1997), 18.

Compiled by Pramaggiore, Performance and Persona, 22-23.

Anaïs Nin, The Diary of Anaïs Nin 1944-1947 (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co, 1971).

Anaïs Nin, The Diary of Anaïs Nin 1944-1947 (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co, 1971).

Anaïs Nin, The Diary of Anaïs Nin 1944-1947 (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co, 1971).

Maya Deren, ‘Film in Progress: Thematic Statement’, Film Culture, no. 39 (1965), 12.

Massimiliano Mollona, ‘Seeing the Invisible: Maya Deren’s Experiments in Cinematic Trance’ 149 (2014). 171.

Sarah Keller, ‘Frustrated Climaxes: On Maya Deren’s “Meshes of the Afternoon” and “Witch’s Cradle”’, Cinema Journal 52, no. 3 (2013), 79.

An amazing artist (always reminds me of my best friend too, and no they're so far away it warmed me to see this)