Dear coven,

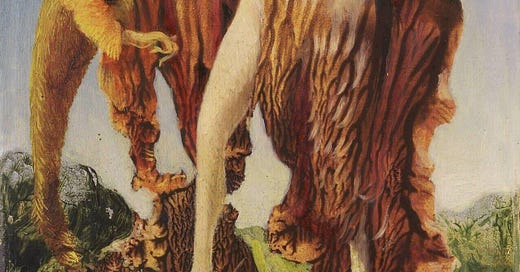

This week’s enchantment is a painting by Max Ernst, which depicts one if his favoured fantastical figures of metamorphosis - the witch. Enchantment of the week is a weekly series in which I introduce a work of art motivated by magic.

As a German living in France in 1939, Ernst was interned as an ‘undesirable foreigner’ in Camp des Milles. Up until that point he had been enjoying a blissful life in Saint-Martin-d'Ardèche with his partner, the painter and writer, Leonora Carrington. While he was released a few weeks later, during the German occupation of France, he was once again arrested, this time by the Gestapo. Fortunately, he eventually managed to escape to America with the aid of Peggy Guggenheim. He fled to the United States in 1941 and it was around this time that he painted The Witch.

Ernst’s work was perpetually motivated by alchemy and magic. As Surrealism’s desire for occultation increased in the later 1930s, the movement’s founder, André Breton likened Ernst to the ‘arch sorcerer’ Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. 1

Ernst viewed his painting as a process of transformation, an alchemical fusion of opposites, hence the fragmentation of bodies, the incongruous juxtapositions, the dreamlike, yet hostile landscape. He invented and utilised a number of techniques to achieve his creations, in this particular piece we can note his use of decalcomania.

Decalcomania was adopted in Surrealism in the 1920s along with key surrealist techniques such as automatic writing, dream recording, and various games that aimed to unleash the power of unconscious. Decalcomania was a process in which glass or paper are pressed into wet paint, which in turn created bubbles.

What had served as an amusing experiment was perfected by Ernst for his art by turning the procedure into a comprehensive system. The resulting images were associated with pictures produced by the unconscious. 2

To the surrealists, magic was a response to the suffering caused by the atrocities of war. The witch’s ability to shift into animals is extended here into the power to morph into natural forms and to dominate the landscape, it is a calling, and a warning. After all, in response to the devastations caused by the war, Surrealism’s founder, André Breton proclaimed:

The time has come to value the ideas of woman at the expense of those of man, whose bankruptcy is coming to pass fairly tumultuously today. It is artists, in particular, who must take the responsibility, … to maximize the importance of everything that stands out in the feminine world view in contrast to the masculine. 3

Breton’s view on female power was…imperfect at best, but that is a topic that I look forward to discussing next Tuesday, so be sure to subscribe to get notified for next week’s enchantment.

If you wish to discover more works motivated by magic, please consider subscribing and following this newsletter’s visual companion.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bibliography

David Lomas, Artist–Sorcerers: Mimicry, Magic and Hysteria, Oxford Art Journal, Volume 35, Issue 3, December 2012, Pages 363–388

Werner Spies, Max Ernst: A Retrospective, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

David Lomas, Artist–Sorcerers: Mimicry, Magic and Hysteria, 375.

Werner Spies, Max Ernst: A Retrospective, 6.

André Breton, Arcanum 17, trans. Zack Rogow (Los Angeles: Green Integer, 2004), 80.

I love this painting - how she looks like a mushroom - and your analysis