Dear coven,

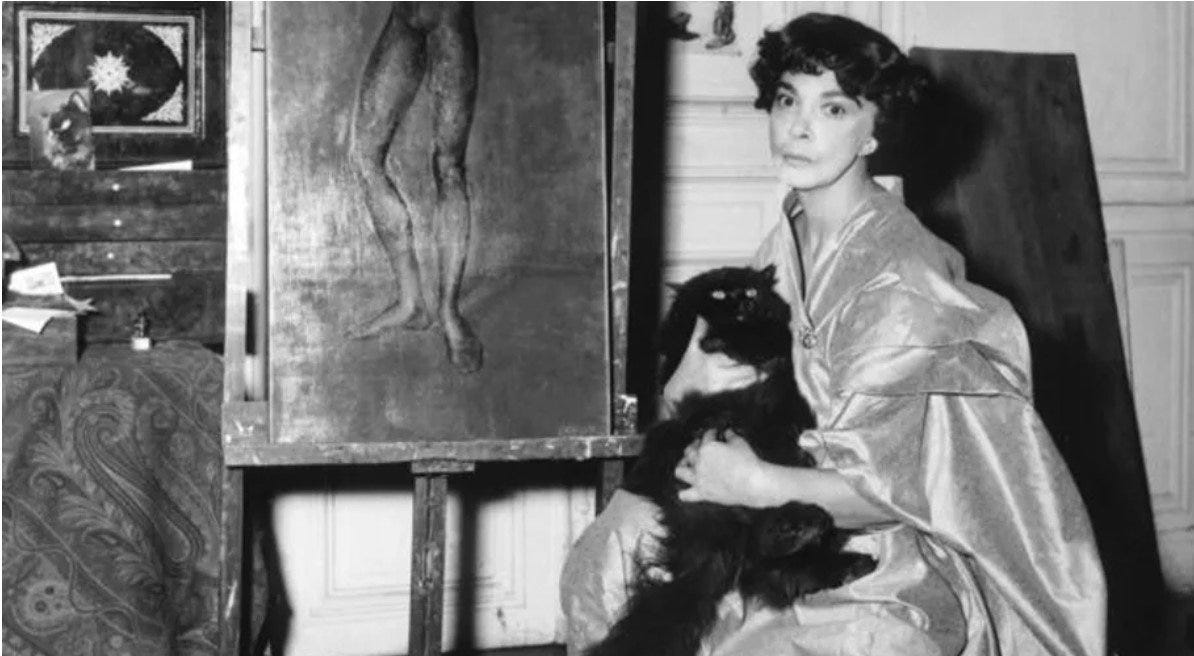

Welcome to enchantment of the week, a weekly series in which I discuss works of art motivated by magic. These usually follow an introduction to the artist from the prior week. You can find last week’s introduction to Leonor Fini here.

Leonor Fini, like a vast number of female artists associated with Surrealism, did not feel at home within the movement. She expressed discontent not against its philosophy, but its inner-working and its male-centric view. Instead of aligning herself with the male surrealist vision, she found solace in friendships with artists who held a liminal position in Surrealism, just like herself. Whitney Chadwick describes this approach as such:

…establishing a subgroup of friends, creating a mini-network of close bonds within the larger group and defining their relationship to Surrealism in terms of friendship and personal affinities. 1

One of the artists within Fini’s network of friends was Leonora Carrington. Carrington and Fini became friends shortly after Carrington arrived in Paris. Carrington had fled the oppression of her family to be with the surrealists and with her partner, Max Ernst. However, conflict within the group pushed the couple away and they soon re-located to a house at St. Martin d’Ardéche. Fini visited them there and she began a portrait of her newly found friend, who Fini claimed was a ‘true revolutionary, but never a surrealist’. 2

The two artists talked for hours in the duration of Carrington’s sitting for Fini, but the project was allegedly abandoned after Carrington attempted to mediate an unpleasant visit by Tristan Tzara, which angered Fini. 3

After 1939 the artists were separated by the war, during which Fini moved through Arcachon, Cannes, Monte Carlo, and finally Rome.

During the war, Fini presented her vision of Carrington in The Alcove, Interior of Three Women (1939). In the painting, an armoured Leonora Carrington appears as a guardian of two female figures on a bed. In Discourse on the Paucity of Reality (1924) André Breton, Surrealism’s founder, dreams of the past: ‘one of these suits of armour seems to be almost my size; if only I could put it on and thereby recover something of the consciousness of a man of the sixteenth century’, and of sleeping women:

I am a man watching this woman sleep. Woman’s sleep is an apotheosis…Is it my fault that women sleep under the stars even as they pretend to keep us by their sides in the luxury of their bedrooms? They hold over us an incredible capacity for failure which, I like to flatter myself, I am able to take into account. As a lake takes into account mayflies. The lake must be charmed by the utter ephemerality of their lives, and as for me, I envy woman her ever-changing view of things. 4

In contrast, Fini depicts Carrington as a warrior who protects the female figures on the bed and asserts a dominant female consciousness that has gone past the conditions of the manifesto and its theories. It has been suggested that Carrington represents the product of alchemical transformation as the androgynous Philosopher’s Stone, hand-in-hand with a surrealist appreciation for opposites. 5

When observing this painting by Fini, one cannot help but consider Carrington’s own self-portrait in which she adorns distinctively male clothing, except for her heeled boots. In Fini’s portrayal of Carrington, a green jacket hangs loosely in her hand, drapery falls to the floor like shed skin, she is wearing a skirt and red socks, her armour has taken the shape of a corset. It is as if Carrington’s vision of the androgynous self, sat on a feminised chair in her Self-Portrait (1937-38), has blended into this image of a woman who wears her femininity as armour. It cannot be certain that the similarity in the clothing’s colour scheme in Carrington’s Self-Portrait and Fini’s The Alcove is intentional, but what becomes apparent is that the view of woman through the female gaze bears a striking difference to male surrealist representation.

In Max Ernst’s Leonora in the Morning Light (1940) we see another representation of Carrington by a fellow artist. However, while Max Ernst does not intentionally attempt to strip Carrington’s power in his painting, by placing her within his own wild and bestial vegetation, she becomes an addition to his sexual power. In his glorification of her image, she becomes a symbol in his oeuvre. Of course, Carrington is also a symbol in Fini’s painting, but the female and male gaze point to a different conclusion, especially when considering that at the time of these paintings’ conception the power dynamic between men and women was incredibly pronounced.

Ernst acts as an illuminator, Fini as an armourer. Ernst’s depiction of Carrington does not push the image of woman further, it places her exactly where she has always been. Meanwhile Fini and Carrington conquer this vision of femininity and completely transform it. They do so by simultaneously enhancing their womanhood and by blurring the lines of the gender binary.

This kind of alchemy was practiced by a number of male surrealists, and indeed Ernst, but as they took what they needed from the feminine to compliment the masculine, women inevitably ended up in a position where they had to fight back for what was taken from them. Carrington herself shared this sentiment:

Women should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning; they must be Taken Back Again, including the Mysteries, which were ours and which were violated, stolen, or destroyed. 6

After the war, Leonor Fini and Leonora Carrington appear re-united in 1952 in a series of photographs by Denise Colomb, but information on their time together is scarce. However, from art produced by Fini, like the painting in question, we can suppose that the ideas they exchanged did not evaporate after their physical separation.

I hope you have enjoyed learning about Fini’s painting. If you wish to learn more about works of art motivated by magic, please consider subscribing to this newsletter.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bilbiography

Breton, André. ‘Introduction to the Discourse on the Paucity of Reality’. Translated by Richard Sieburth and Jennifer Gordon. October 69 (1994): 133–44.

Carrington, Leonora, Edward James, and Inés Amor. Leonora Carrington : A Retrospective Exhibition. New York: Center for Inter-American Relations, 1976.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. London: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Grew, Rachel. ‘Leonor Fini and Dressing UP’. Woman’s Art Journal 40, no. 1 (2019): 13–20.

Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (London: Thames and Hudson, 1985), 44.

Fini in Chadwick, Women Artists, 66.

Chadwick, Women Artists, 66.

André Breton, ‘Introduction to the Discourse on the Paucity of Reality’, trans. Richard Sieburth and Jennifer Gordon, October 69 (1994), 137.

Rachel Grew, ‘Leonor Fini and Dressing Up’, Woman’s Art Journal 40, no. 1 (2019), 15.

Leonora Carrington, Edward James, and Inés Amor, Leonora Carrington : A Retrospective Exhibition (New York: Center for Inter-American Relations, 1976), 23.

Ah, when two great minds meet!!!!!!!

!!!!!