Leonor Fini always wanted to be a Sphinx. As a child she was fascinated by mythological figures and she encountered them often - there was the Egyptian Sphinx of Miramare Castle, the caryatids of Eden cinema in Trieste, and, of course, there were the Sphinxes living in her imagination. Fini appreciated the Sphinxes as images of femininity triumphing over the city. 1

This week I have chosen to highlight Leonor Fini. An artist associated with Surrealism, but one that paved a path of her own, much like her peers Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington.

Leonor Fini was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Her mother fled her domineering father and they both moved to Trieste in Italy while Fini was an infant.

Fini grew up in an upper-middle class household which introduced her to art and music, though her relatives were unhappy with her choice to become an artist. She claimed that as soon as she began painting what was in her head the people around her were shocked. 2 Similarly to Leonora Carrington, before she undertook her formal education, Fini had studied art by flipping through books and visiting museum. 3

At the age of seventeen she left her family home for Milan and her interest in the unconscious led her to Paris and Surrealism in 1931. At the time, she was already well-versed in Freud, Novalis and the German Romantics. She noted that many of the surrealists were surprised by her knowledge:

I, an Italian girl, had already read all the published works of Kafka in German as well as Jensen’s Gradiva, and most of the writings of Freud, all of which were quite new in Paris, but in Trieste, had been part of our heritage as Austrian citizens until the end of the First World War. 4

Fini had an affinity for Surrealism’s exploration of hidden correspondences, but never officially joined the group and vehemently opposed Breton’s authoritarian attitude:

I disliked the deference with which everyone treated Breton. I hated his anti-homosexual attitudes and also his misogyny. It seemed that women were expected to keep quiet…yet I felt that I was just as good as the men…I never saw the point of being part of one group, and I refused the label Surrealist. I preferred to walk alone. 5

Even though she rejected her affiliation with the group, Fini formed a close bond with her female peers. She felt a need for community over a desire for monogamous romantic relationships with men:

I have never lived with just one person. Since I was 18, I have preferred to be in a sort of community - a big house with my atelier and cats and friends, and with one man who was rather a lover and another who was rather a friend. And it has always worked. 6

Akin to how Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington transformed the kitchen space into an alchemical laboratory and the crone into a feminist symbol, Fini performed transmutations of her own. In particular, with her personification with the Sphinx, a mythical figure that already held a significance to the surrealists with its potential for marvelous encounter and forbidden desire. As Surrealism’s founder, André Breton posed:

‘Have we not known for a long time that the riddle of the Sphinx says much more than it seems?’. 7

Fini approached the Sphinx through a matriarchal point of view alongside a fascination with the being that she developed in her childhood. In 1951, Fini was able to visit Egypt, though even before her trip she had depicted herself as a shepherdess of the creatures in The Shepherdess of the Sphinxes (1941), taking her childhood fascination and presenting it as a powerful image of the self.

It is clear from looking at this work that Fini desired to take charge of the narrative regarding female representation. One could interpret her stick as a reclamation of her sexual autonomy. When painting women, Fini portrayed them as erotic, but powerful, taking back the sexuality that had been stolen and viewed through a male gaze.

We see this further in Sphinx Philagria (1945) which portrays the Sphinx as feminised Nature, but while her wild hair and naked breasts hint at youth, the overcast sky and threatening vegetation stand in contrast:

‘Woman and Nature are one, as woman is rooted to the soil. Together they symbolise the potential for life, despite death’. 8

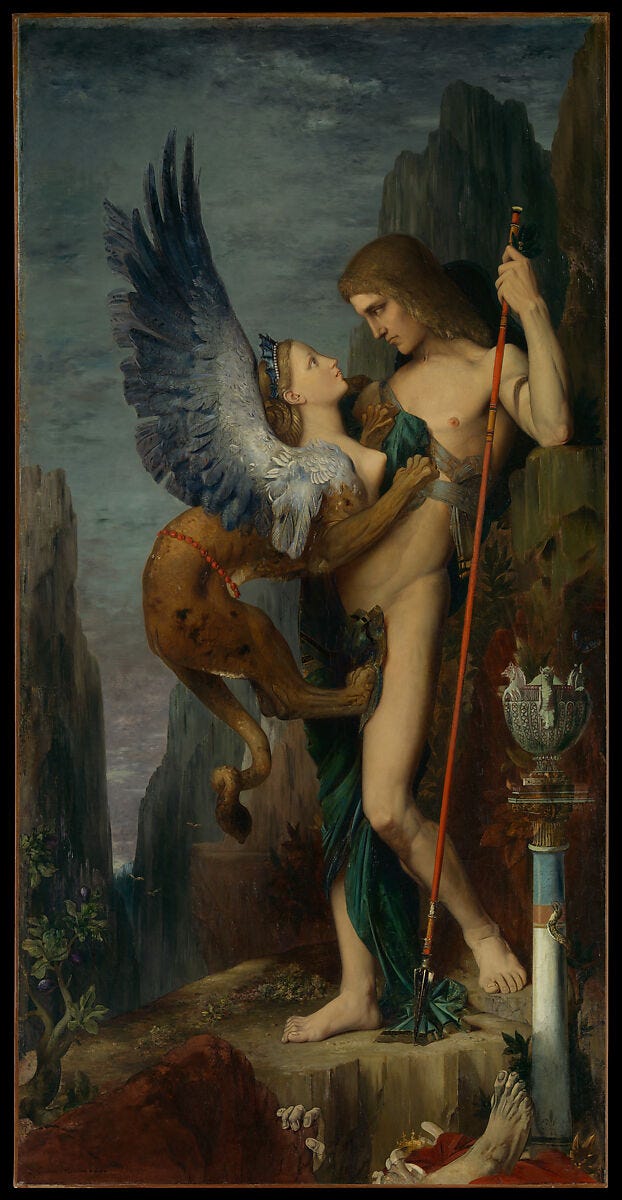

Fini’s Sphinxes stand in contrast to earlier nineteenth century paintings such as Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864) by Gustave Moreau. Unlike Moreau, Fini gives a voice to the Sphinx, not Oedipus. To her, this symbol of womankind is not simply a problematic riddle, as suggested by Freud, her interpretations is closer to Nietzsche: ‘Which of us is Oedipus here? Which of us Sphinx? It is, it seems, a rendezvous of questions and question marks’. 9

Fini took these question marks as an opportunity to blend the feminine and masculine, the human and animal, blurring the distinctions between the two opposing forces in an act of matriarchal mythologisation, as Fini spoke of herself:

‘I am against society, eminently asocial, and I am linked to nature like a witch rather than as priestess. I am in favour of a world where there is little or no sex distinction’. 10

In her defiance to accept the Sphinx as a problem to be solved, she opposed the view male Surrealism held on women as ‘the most wonderful and disturbing problem in all the world’. 11

I hope you have enjoyed reading a little bit about Leonor Fini. If you wish to learn more about artists influenced by magic, please consider subscribing and following the visual companion on Instagram. I’d be curious to know what feelings Fini’s paintings evoke in you, so do let me know in the comments.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bibliography

Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Breton, André. ‘The Legendary Life of Max Ernst, Preceded by a Brief Discussion on the Need for a New Myth’. Edited by Charles Henri Ford. View 2, no. 1 (1942): 5–7.

Grew, Rachel. ‘Sphinxes, Witches and Little Girls: Reconsidering the Female Monster in the Art of Leonor Fini’. Loughborough University, 2010.

Jelenski, Constantin. Leonor Fini Peinture. Paris: Editions Mermoud, 1980.

Kent, Sarah. ‘Leonor Fini: Surreal Thing’. The Telegraph, 30 October 2009. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-features/6467290/Leonor-Fini-surreal-thing.html.

Mahon, Alyce. ‘La Feminité Triomphante: Surrealism, Leonor Fini, and the Sphinx’. Dada/Surrealism, no. 19 (2013): 1–20.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Beyond Good and Evil. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973.

Roditi, Edouard. ‘A Paris Interview with Leonor Fini, Europe’s Leading Surrealist Painter’. Art Voices 2, no. 10 (1963): 204–21.

Täljedal, Brita, Cecilia Andersson, and Anna Rådström. Leonor Fini: Pourquoi Pas? Umeå: Bildmuseet, 2014.

Webb, Peter. Sphinx: The Life and Art of Leonor Fini. Paris: The Vendome Press, 2009.

Winter, Nina. Interview with the Muse. New Alresford: Moon Books, 1978.

Webb, Sphinx: The Life and Art of Leonor Fini, 102.

Nina Winter, Interview with the Muse (New Alresford: Moon Books, 1978), 57.

Brita Täljedal, Cecilia Andersson, and Anna Rådström, Leonor Fini: Pourquoi Pas? (Umeå: Bildmuseet, 2014), 18.

Leonor Fini in Edouard Roditi, ‘A Paris Interview with Leonor Fini, Europe’s Leading Surrealist Painter’, Art Voices 2, no. 10 (1963), 221.

Peter Webb, Sphinx: The Life and Art of Leonor Fini (Paris: The Vendome Press, 2009), 69-72 .

Fini cited in Sarah Kent, ‘Leonor Fini: Surreal Thing’, The Telegraph, 30 October 2009.

Breton, The Legendary Life, 5–7.

Mahon, La Feminité Triomphante, 10.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, trans. R.J. Hollingdale (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973), 15.

Translation of the text from Jelenski, Leonor Fini: Peinture, Paris: Editions Mermoud Vilo, 1980 in Alyce Mahon, ‘La Feminité Triomphante: Surrealism, Leonor Fini, and the Sphinx’, Dada/Surrealism, no. 19 (2013), 17.

André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972), 180.

So so rich && wonderful.