Remedios Varo believed in magic.

During an evening stroll down the streets of Mexico City, the artist stumbled upon a market stall. There, she encounteted a plant with distinctly egg-shaped fruits. She did not hesitate in purchasing this peculiar specimen. Once home, she took the plant to her terrace, already populated with greenery of all sorts. She placed it under the moonlight, gathered her paint tubes and meticulously arranged them around the plant. Varo felt that the arrangement of the plant and the paints would reach a harmonious union under the moonlight, and that their conjunction would prove favourable for the next day of painting. 1

Superstitious, deeply empathetic, attuned to nature and all together magical, Remedios Varo will always hold a place in my heart, and that is why I have chosen to highlight her this week.

Remedios Varo was born in Anglés, but her family moved to Madrid when she was nine. She had two brothers and an intensely Catholic mother who named her after the patron Saint of her hometown, the Virgin of Los Remedios. Her father, a hydraulic engineer, instructed her to copy detailed drawings and diagrams to learn the techniques of mechanical drawing. 2 As a child, Varo sunk herself into books with a preference for the adventures of Jules Verne and the mysteries of Edgar Allan Poe.

She was introduced to the Parisian surrealist circle in 1935 while sharing a studio with Esteban Francés. Varo revealed a sense of non-belonging amongst them:

Yes, I attended those meetings where they talked a lot and one 'learned various things; sometimes I participated with works in their exhibitions; my position was one of a timid and humble listener; I was not old enough nor did I have the aplomb to face up to them, to a Paul Éluard, a Benjamin Péret, or an André Breton. I was with an open mouth within this group of brilliant and gifted people. I was together with them because I felt a certain affinity. Today I do not belong to any group; I paint what occurs to me and that is all. 3

While Varo did not find a home within Surrealism, she discovered it elsewhere – in Mexico and in her friendship with Leonora Carrington. Both artists fled to Mexico during WWII, and once they found each other there, they hardly spent a day apart.

In her first few years in Mexico, Carrington produced a multitude of watercolours, one addressed Varo with the words:

Remedios, I told you that I made a spell against (the evil eye) there it is – yesterday evening I had a fever, auto-suggestion perhaps - I don’t feel well enough to go out – Come see me if you can? 4

Carrington responded to the atmosphere of Varo’s home which has been described as populated with cats and filled with talismans, shells, crystals, and trinkets. In Mexico, Carrington and Varo breathed magic into their domestic spaces through culinary experiments that they believed to be alchemical cooking. Carrington had previously experimented with cooking by conniving culinary pranks such as serving omelettes filled with people’s own hair, cut while they were sleeping, and preparing meals so extravagant barely anyone would dare eat them. 5 Now coupled with Varo she had a sidekick for her pseudoscientific kitchen investigations.

While the friendship offered sense of stability, Varo suffered from severe anxiety and fear of moving, she did not even dare stray outside her neighbourhood. 6

In the artist’s paintings, one can see a reconciliation of her anxieties of displacement and the childhood yearning for journeys, as the characters on her canvases embark on spiritual quests.

Exiled from her homeland, Varo began a pilgrimage of her own. Her vast interests – science, magic, astrology, alchemy – all played a part in her investigations. In Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River (1959), Varo’s river indicates a search for the self and enlightenment. This painting veers away from the traditional mode of a hero’s or a heroine’s journey as there seems to be no one who has assigned the figure’s task of crossing the river and seeking its source. There is no one to guide her but her compass. Only the sombre crows observe her travels, the actions of Varo’s heroine are entirely self-motivated.

This is a factor in many of her paintings, there are no helpers, no heavy involvement with the opposite sex, no visible mother and father figures, nor are there perilous tasks, only treacherous journeys.

If any one thing in particular moves Varo’s narratives, that would unmistakably be music. For instance, in Varo’s Solar Music (1955) a barefoot figure, dressed in a mossy robe, plays music on the strings of a sunbeam that shines on the forest floor; its melody brings life to the brambles, weeds and roots.

This woodland character needs no initiation to play music, if the act is a task of awakening the forest, the figure does so of its own volition. This is a gesture of empathy and intuition - note that the sun has breached the cloud cover, but does not demand to be played, it offers its power up to one that is attuned to the harmonious virtue of nature.

Within the branches of the trees in Solar Music, we can spot red birds, their flight seemingly activated by the melody. In her paintings, the human and the natural persist and unite through music. What is dead or asleep comes back to consciousness through rhythm.

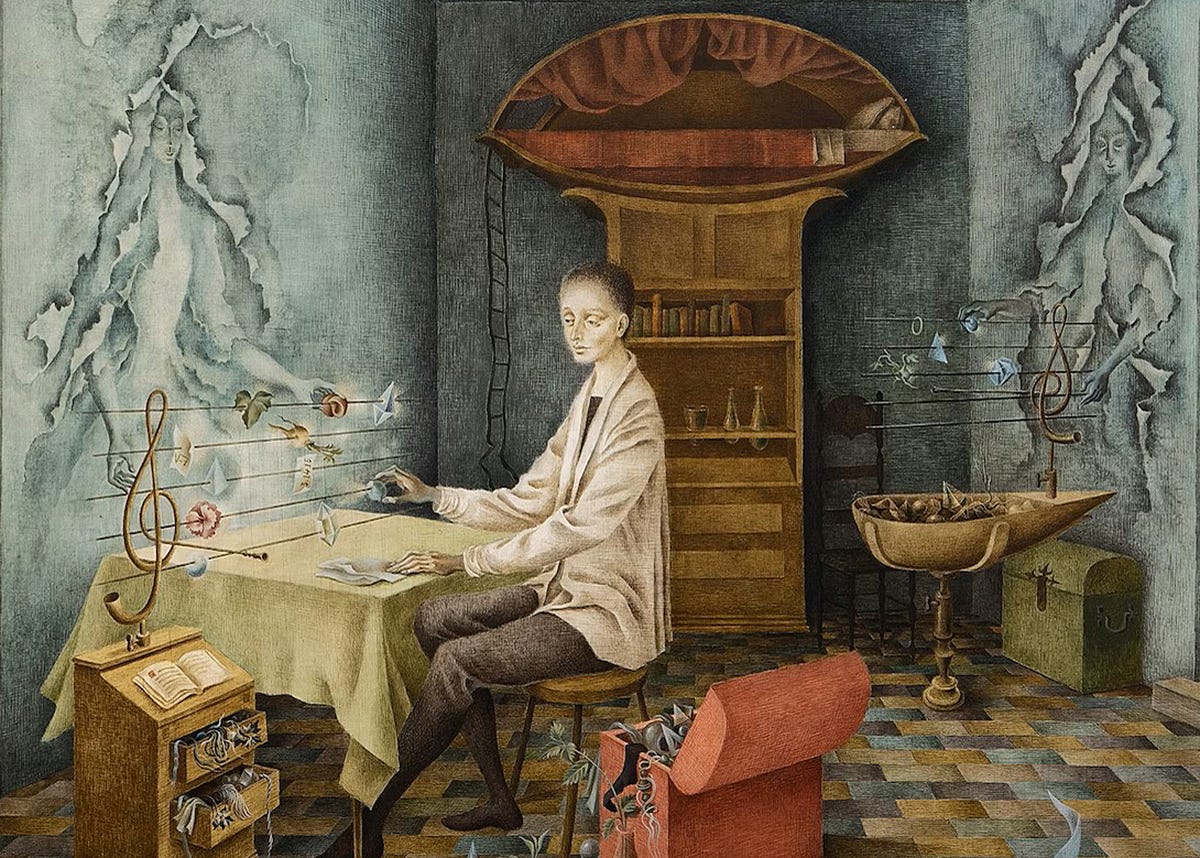

Again, we see Varo weaving together rhythmic, magical activity in Harmony (1965) which illustrates an androgynous figure in a medieval study filled with alchemical equipment. The figure composes objects from a treasure chest onto a treble clef, musical harmony is born out of the possibilities of chaos.

Varo’s Harmony, much like Solar Music, expresses a Pythagorean vision of the music of the spheres. 7 The idea of this system is that understanding musical harmony can equate to understanding universal harmony. This theory appears in Pliny, Ptolemy, Cicero and a considerable number of writers. The spheres in this hypothesis refer to celestial bodies and their movements, a tenet of Pythagoreanism:

According to Plato the world soul was constructed on a numerical plan. The numbers involved are one, two, three and their squares and cubes. This is purely Pythagorean philosophy. The number relations and combinations introduced by Plato are the same as those associated with the Pythagorean system of musical intervals. Although Plato does not mention the music, the word harmony does occur. 8

Varo’s use of sacred numbers and music in tandem, highlights her knowledge of Pythagorean and astrological doctrines, which she utilised to portray a bond between the human and the cosmological. When discussing Harmony, Varo confirmed the interrelations between these theories and her work:

The character is trying to find the invisible thread that unites all things, that’s why he’s stringing together, on a musical staff of metal threads, all kinds of objects: from the simplest scrap of paper containing mathematical formula, which is in itself a great jumble of things. 9

Music drives the actions and quests on Remedios Varo’s canvases and it is a motif that illustrates the esoteric ideas she explored. And Varo was, undoubtedly, driven by magic in her own life.

I hope you have enjoyed reading a little bit about Remedios Varo. If you wish to see more articles on artists influenced by magic, please consider subscribing to this newsletter and following its visual companion.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles:

bibliography

Chadwick, Whitney. Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

Carrington, Leonora, and Marina Warner. The House of Fear: Notes from Down Below. Michigan: E.P. Dutton, 1988.

Haynes, Deborah J. ‘The Art of Remedios Varo: Issues of Gender Ambiguity and Religious Meaning’. Woman’s Art Journal 16, no. 1 (1995): 26–32.

Kaplan, Janet. ‘Remedios Varo: Voyages and Visions’. Woman’s Art Journal 1, no. 2 (1980): 13–18.

Kaplan, Janet. Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys. New York: Abbeville Press Inc, 2000.

Kinkeldey, Otto. ‘The Music of Spheres’. Bulletin of the American Musicology Society, no. 11/12/13 (1948): 30–32.

Nochlin, Linda. ‘Art and the Conditions of Exile: Men/Women, Emigration/Expatriation’. Poetics Today 17, no. 3 (1996): 317–37.

Sánchez Lacy, Alberto Ruy, Michelle Suderman, Octavio Paz, Eliot Weinberger, Lelia Driben, Carole Castelli, Wolgang Paalen, et al. ‘Mexico in Surrealism: Creative Transfusion’. Artes de México, no. 64 (2003): 65–80.

Santos-Philips, Eva. ‘Questioning and Transgressing in the Representations of Silvina Ocampo and Remedios Varo’. Hispanic Journal 25, no. 1/2 (2004): 155–70.

Tibol, Raquel. ‘Artes Plásticas: Primera Investigación de Remedios Varo’. Novedades, July 1957, sec. México en la Cultura.

Kaplan, Remedios Varo: Voyages and Visions, 13.

Kaplan, Remedios Varo: Voyages and Visions, 14.

Raquel Tibol, ‘Artes Plásticas: Primera Investigación de Remedios Varo’, Novedades, July 1957, sec. México en la Cultura.

Chadwick, Women Artists, 195.

Leonora Carrington and Marina Warner, The House of Fear: Notes from Down Below (Michigan: E.P. Dutton, 1988), 15.

Nochlin, Art and the Conditions of Exile, 319.

Haynes, The Art of Remedios Varo, 30.

Otto Kinkeldey, ‘The Music of Spheres’, Bulletin of the American Musicology Society, no. 11/12/13 (1948), 30.

Remedios Varo in Lara Balikci, ‘Harmony, 1956’, in Remedios Varo (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2023), 54.

![Remedios Varo - musica solar [1955] | Remedios Varo - musica… | Flickr Remedios Varo - musica solar [1955] | Remedios Varo - musica… | Flickr](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!tvV_!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8554636d-e867-4a35-9d4b-34c08b811689_696x1024.jpeg)

Okay, seriously? I had mentioned previously that I liked Carrington and I was thinking of sending you a message asking if you had written much about Varo and now here she is! She is my favorite surrealist painter by far (I'm not even really into surrealism) because of all her magical imagery and odd figures. I actually did an art study with some of my older students (5th graders) a couple years ago and they were fascinated by her, and hearing their interpretations of her paintings was so eye-opening.

I recall seeing some of Remedios and Leonora's paintings at Tate Modern a few years ago. They were absolutely fascinating, and I was really wowed, especially because of the time I wasn't familiar with none of their work, in fact I was just finding out about their existence in the surrealist art world. Thanks for sharing this beautiful article. :)