Dear coven,

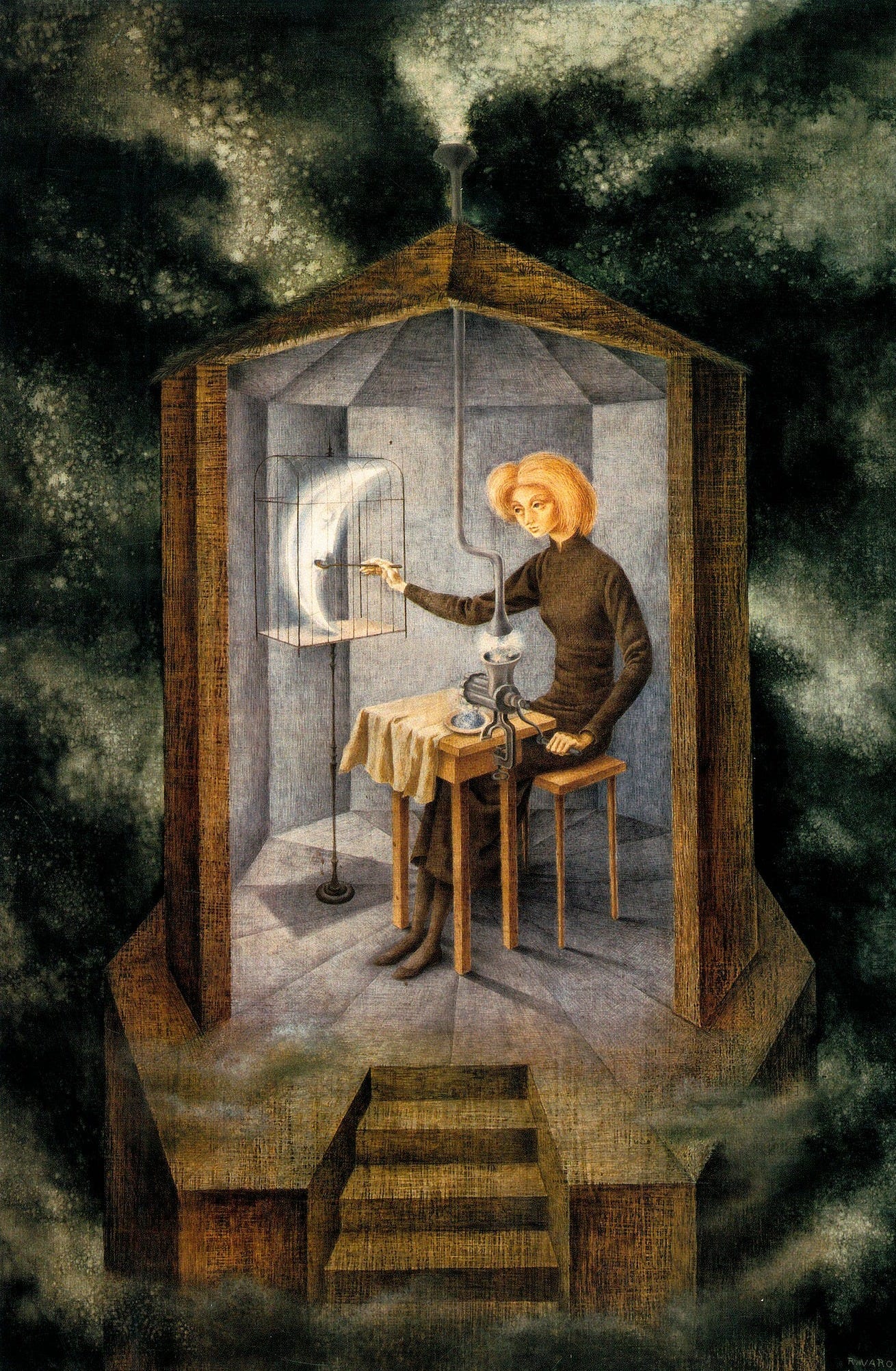

I chose Remedios Varo’s Celestial Pablum (1958) as this week’s enchantment due to the very emotional response it can incite. Enchantment of the week is a weekly series in which I cover works of art motivated by magic, these usually follow an introduction to the artist from the prior week. In this instance, you can read last week’s introduction to the work and life of Remedios Varo here.

In this painting, we see a solitary young woman in a tower. She is grinding star matter into a pablum to feed a crescent moon in a cage. Both the moon and the woman are isolated within their space and in the universe as a whole. It has been interpreted that this painting depicts the never-ending work of woman as nurturer, as the key figure takes on a ‘traditional role as she performs the timeless maternal ritual of feeding’. 1

Varo did not experience motherhood herself. She became pregnant in France, but her economic circumstances led her to have a botched abortion that destroyed her chances of bearing children. Despite not being able to have children, Varo remained devoted to the children of her friends and relatives, such as Leonora Carrington. 2

The fear of a loss of autonomy due to motherhood is evident in numerous pictorial representations by female artists, whether they had children or not. While Carrington embraced motherhood, she still lamented on its burden:

I always continued to paint, even when the children were very small. Only when they were ill, I dropped everything, and my children became my priority. But often I said to my friend Remedios: ‘We need a wife, like men have so we can work all the time and somebody else would take care of the cooking and the children’. 3

The cooking and the children, however, clearly made their way into her work. This is evidenced in the use of egg tempera by mixing an egg yolk into her paint, mimicking culinary procedures, and in her drawings of wonderous creatures that covered the walls of her home, created to supplement the stories she told her children. As an artist concerned with images and stories of her own childhood, perhaps bearing children of her own offered a creative opportunity. Carrington did not conform, instead, her work continued to fight against the restrictive labels put on women, including that of nurturer.

Meanwhile, Leonor Fini demonstrated a total rejection, defining herself as ‘Lilith, the anti-Eve’; physical maternity repulsed her. In September 1947 she underwent a hysterectomy for medical reasons and claimed that she was happy to have undergone this operation, as having children horrified her. 4

Surrealism, as a predominantly male movement, allowed all the fantasies of a femme enfant but left little room for maternity. As discussed by Whitney Chadwick:

The imagery of the sexually mature, sometimes maternal woman has almost no place in the work of women Surrealists. Conflict arises in the women artists' attempt to reconcile traditional female roles with lives as artists in a movement that prizes the innocence of the child-woman and violently attacked the institutions of marriage and the family. 5

Jacqueline Lamba did not paint for a decade after giving birth and did not exhibit her work until her separation with André Breton, Surrealism’s founder. Eileen Agar had a resistance to motherhood ever since she was an adolescent. Frida Kahlo did not wish to bring a child into her already intense marriage with Diego Rivera. 6

Remedios Varo clearly recognised the complexities but strongly disproved the idea that motherhood and art should be incompatible (as did her female peers, whether they wished to become mothers or not).

Celestial Pablum offers an empathetic look at the loneliness of the nurturer figure. Varo created an image that often provokes audible gasps of recognition when shown to a female audience, as one woman put it:

‘I knew then that she [Varo] was talking about me and my kitchen, and my moon babies and the stars I grind’. 7

It is also significant that the image of the moon itself is traditionally associated with feminine energy. In folklore women are often associated with the moon, the same can be observed in Christianity’s view of Christ as the sun and the Virgin Mary as the moon. 8 In The Great Mother, Erich Neumann discusses the spiritual symbol of the matriarchal sphere as the moon and the mystery of transformation. He credits this mystery to the ‘Great Round’, in which positive and negative, male and female, and all opposites in the universe are intermingled. Neumann suggests that unlike the Apollonian-solar-patriarchal spirit, the matriarchal spirit does not negate its bond with the Earth Mother:

For this reason, the favoured spiritual symbol of the matriarchal sphere is the moon and its relation to the night and the Great Mother of the night sky. The moon, its luminous aspect of the night, belongs to her; it is her fruit, her sublimation as light, as expression of her essential spirit. 9

While this painting demonstrates a vision of motherhood, Varo also placed an emphasis on the power of women as creators within her work through imagery of eggs, tubes, wombs – to refer not to physical reproduction but to the process of producing, of rebirth, of creation of self.

If you wish to discover about more works motivated by magic, please consider subscribing and following this newsletter’s visual companion.

Thank you for reading!

Tip Jar ☕

Recent articles

bibliography

Chadwick, Whitney. Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1990).

Grew, Rachel. ‘Sphinxes, Witches and Little Girls: Reconsidering the Female Monster in the Art of Leonor Fini’. Loughborough University, 2010.

Kaplan, Janet. Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys. New York: Abbeville Press Inc, 2000.

Mirkin, Dina Comisarenco. ‘To Paint the Unspeakable: Mexican Female Artists’ Iconography of the 1930s and Early 1940s’. Woman’s Art Journal 29, no. 1 (2008): 21–32.

Mulder, Nan. ‘Leonora Carrington in Mexico’. Alba 1, no. 6 (1991): 6.

Neumann, Erich. The Great Mother. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955.

Santos-Philips, Eva. ‘Questioning and Transgressing in the Representations of Silvina Ocampo and Remedios Varo’. Hispanic Journal 25, no. 1/2 (2004): 155–70.

Eva Santos-Philips, ‘Questioning and Transgressing in the Representations of Silvina Ocampo and Remedios Varo’, Hispanic Journal 25, no. 1/2 (2004), 164.

Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991), 131.

Nan Mulder, ‘Leonora Carrington in Mexico’, Alba 1, no. 6 (1991), 6.

Rachel Grew, ‘Sphinxes, Witches and Little Girls: Reconsidering the Female Monster in the Art of Leonor Fini’ (Loughborough, Loughborough University, 2010), 3.

Chadwick, Women Artists, 296.

Chadwick, Women Artists, 131.

Janet Kaplan, ‘Remedios Varo’, Feminist Studies 13, no. 1 (1987),160.

Dina Comisarenco Mirkin, ‘To Paint the Unspeakable: Mexican Female Artists’ Iconography of the 1930s and Early 1940s’, Woman’s Art Journal 29, no. 1 (2008), 29.

Erich Neumann. The Great Mother. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955, 56-57

Eva Santos-Philips, ‘Questioning and Transgressing in the Representations of Silvina Ocampo and Remedios Varo’, Hispanic Journal 25, no. 1/2 (2004), 164.

Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (London: Thames and Hudson, 1985), 131.

Nan Mulder, ‘Leonora Carrington in Mexico’, Alba 1, no. 6 (1991), 6.

Rachel Grew, ‘Sphinxes, Witches and Little Girls: Reconsidering the Female Monster in the Art of Leonor Fini’ (Loughborough, Loughborough University, 2010), 3.

Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art and Society (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997), 296.

Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists, 130-131.

Janet Kaplan, ‘Remedios Varo’, Feminist Studies 13, no. 1 (1987), 160.

Dina Comisarenco Mirkin, ‘To Paint the Unspeakable: Mexican Female Artists’ Iconography of the 1930s and Early 1940s’, Woman’s Art Journal 29, no. 1 (2008), 29.

Erich Neumann, The Great Mother (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), 56-57.

I love this exploration. The reconciliation between the identities of woman/mother and artist is so complex and interesting (and hits home for me) and steeped in something otherly-dimensional. Thanks for sharing!

I love Varo’s work. This is a very interesting article. Thank you for sharing!!